Long(ish) essays on horror stuff, written by our editors.

Beware: Spoilers. We go into every post assuming you’ve already seen any media we might bring up. Complaints about spoilers will be ignored and possibly mocked in public. Enjoy reading!

On the surface, the ending of the 1920 classic silent film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari seems to be contradict the anti-authoritarian themes throughout the rest of the film—and in German Expressionism more broadly. But the lingering strangeness of the sets and that final, sinister shot of the Director suggest that the frame story is a deliberate deception, not merely something tacked on against the will of the writers that totally screws up their otherwise-masterpiece. As a bit of meaningful misdirection, the frame subverts our expectations and demands reinterpretation.

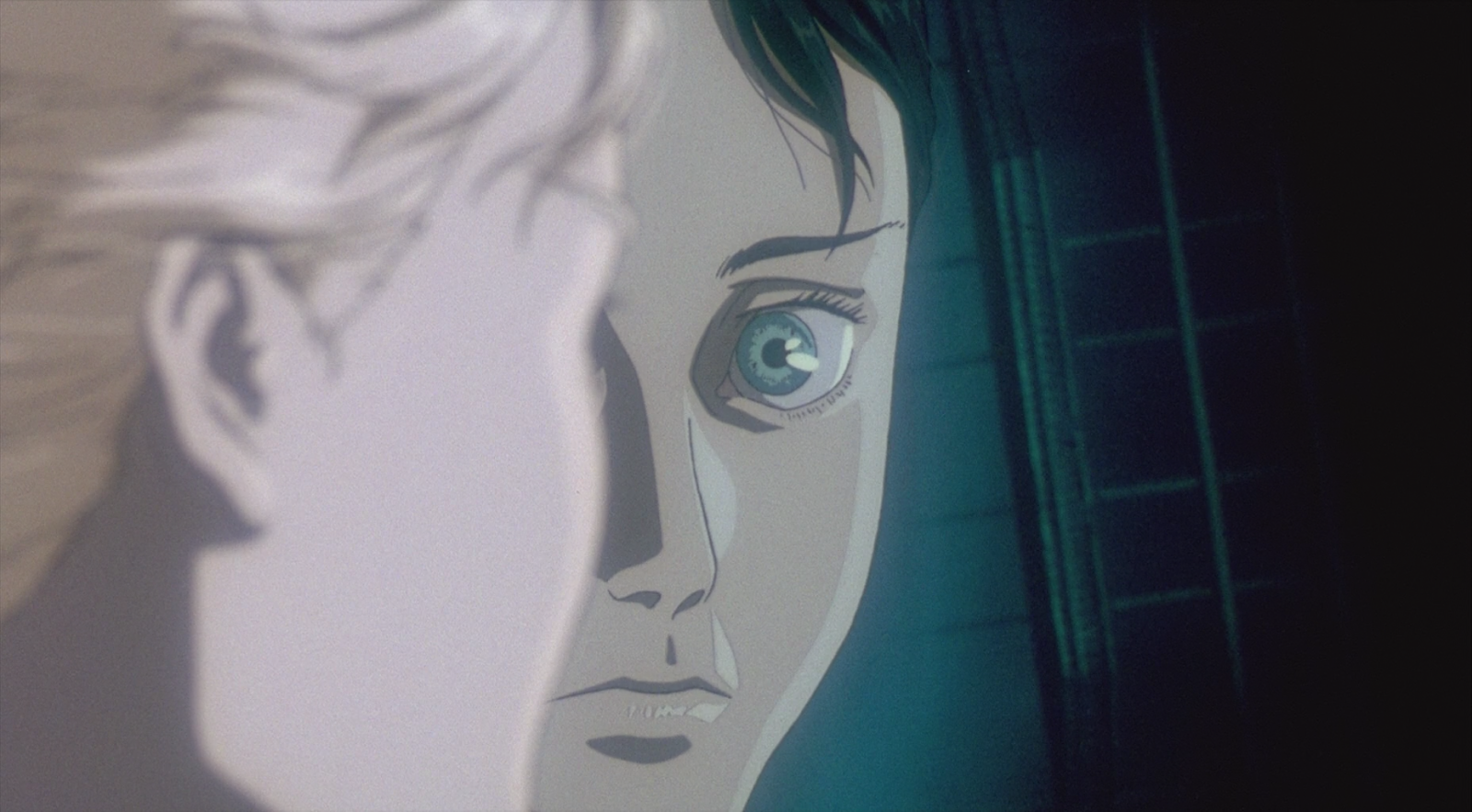

Perfect Blue likes to jar audiences out of escapism and suspension of disbelief as a way to get us to think critically about the film as a film—as a story, a fantasy, a constructed narrative. When you engage with the film in this way, assuming the film itself knows it’s a film, the nature of the story changes. It becomes clear that the film’s “reality” has been invaded by a surreality brought on by fan obsession with the fantasy of a J-pop idol. That fantasy comes to literal life in the film, as a metaphor for the real-life dangers of immersion, suspended disbelief, and escapism in the arts.

Richard Adams Watership Down and its 1978 animated adaptation carries an environmental message of letting nature run its course that can feel quaint in a world of ongoing and drastic human-caused climate change. But its humans, especially in the book, are incomprehensible, godlike creatures bringing death, destruction, and madness to the creatures they touch. In that context, the quaint message becomes heartbreakingly nostalgic for a time when stepping away from nature and letting it run its course might have been possible.

The 2019 Netflix film I Am Mother received a lot of attention at the time of its release for being an expertly crafted film with a small, but very talented cast, and spot on special effects. Sprinkled through the positive reviews, though, are claims that it’s an anti-abortion screed (or an “artful” take on “pro-life themes,” depending on the critic writing about it). We explain why it’s definitely not anti-abortion, as well as what it’s actually about: robots being bad at ethics.

Ghost in the Shell tells the story of humanity's crossing the event horizon that draws us into a spiral toward meaninglessness and slow oblivion as we approach the technological singularity.

All three shorts in this bizarre collection develop shared and interrelated themes that, taken together, tell a narrative of environmental horror brought on by modern human greed, materialism, and self-delusion about the doom we’ve created.

Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) has been called the most controversial film in Hollywood history. Not just controversial for its time, Russell’s masterpiece remains shocking to this day in its depictions of cruelty, orgiastic sexuality, the evils of the 17th-century Catholic Church, and blasphemous imagery.

The film tells an old historical truth about political martyrs … and gets censored for it.

The ham-fistedness of Ready or Not fits the carefully-crafted and well-paced balance of quippy, campy, self-aware pulp horror/comedy. The film doesn’t waste a single moment of screen time and pays close attention to the arcs of its three main characters through the deconstruction of Grace's wedding dress as she finds herself hunted in The Most Dangerous Game: Satanic Mansion Edition.

Rosemary’s Baby and the films that have followed it draw clear lines between Satanic cults and capitalism. They tell stories about the evils that unchecked, late-stage capitalism incentivizes: selfishness, greed, ruthlessness, and the sacrifice of others for status, wealth, power, and privilege.

There’s a rich film tradition drawing on and indulging humanity’s long and ongoing history of Satanic panics. In We Summon the Darkness (2019), though, the Satanists we need to watch out for are a congregation of Christians following a televangelist who fancies himself “the wrath of God.” That man, Pastor John Henry Butler is, in our reading of the film, the physical embodiment of Satan on Earth. The fallen Lucifer, warped by pride and a lust for power.

While not a sequel or adaptation, The Cured expands on the themes of the Living Dead franchise. It does this by drawing from the fast zombie tropes established in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and by returning to the source material behind the source material. The Cured goes beyond Night of the Living Dead (1968) and looks to the novel that inspired it: Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954).

Zombies are an undead funhouse mirror, a decrepit parody of humanity meant to reflect our worst traits back at us. Part of that critique means that real, living, breathing humans, should always be more dangerous than stupid, slow-moving zombies. Today, Meg unpacks and celebrates the Romero zombie for all its given us. She also has fun hating on Zack Snyder’s fast zombies.

The character of Barbra in 1968’s Night of the Living Dead has been mostly viewed as a useless waste of screentime, thankfully revised into a final girl action hero in the 1990 remake. We’re here to argue, as much as we love action hero Barbara (with the extra “a”), original Barbra’s reputation is undeserved. She’s a realistic character type who should have more of a place in horror and who, when present, deserves to live every once in a damn while.

The film takes place over the wedding and reception of a Polish woman and a British-born Polish man. Before the wedding, Piotr discovers a skeleton buried in the yard behind their new home, the old house Żaneta inherited from her grandfather. Demon is about a terrible truth that these wedding guests and many Poles want to forget, one that persists in the bones under the very soil of Poland itself.

While not technically an adaptation or a remake, Get Out re-envisions The Stepford Wives--both the 1972 novel and the 1975 film--in what you could call a remake in spirit. (Oh, and it rightly ignores the 2004 atrocity.)

Forbes’ film and Levin’s novel dealt with feminist themes of gender power dynamics, ownership of female bodies, and the objectification of women. Get Out builds on how those issues intersect with racial power dynamics, ownership of Black bodies, and racist ideas of Black people as animals.

But Peele’s up to more than just swapping Women’s Liberation for Black Emancipation. He gives us a more hopeful film, lighter and funnier than The Stepford Wives, but at the same time heavier and more horrifying.

Ira Levin’s novel, The Stepford Wives, adapted to film in 1975 and again in 2004, marries comedy with the grotesque. That satire gives the book and its underlying feminism their power. The films miss this point in opposite ways. The ‘75 version downplays the humor, ignoring the absurdity of the novel’s premise, and the ‘04 version plays everything for laughs, seeming to mock the novel’s feminism.

Parasite climaxes in tragic chaos because of the systems that dehumanize and punish lower class families, while actively preventing them from advancing toward social ideals of “success.” Beneath the satirical madness of Bong’s film lies the tragic truth: the hard lines of class are nearly impossible to transcend, and attempting to cross them might leave you worse off.

Everything in Eraserhead folds back on the protagonist, Henry Spencer. Every disturbing image, grating sound, jarring scene change, and bizarre dialogue tells us what’s happening in the film and what’s happening in his head, a terrible, body-horror inflected vision of paternal postpartum depression.

Guillermo del Toro’s fantasy horror classic, Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), is a coming-of-age story about Ofelia, a girl living in the fascist Spanish regime of Francisco Franco as an imperiled pregnancy brings about her mother’s death. In the end, Ofelia grows--she transcends these horrors--not by giving up childish fantasies, as she’s told to do, but by learning from them to hold to her convictions, keep her own counsel, and make moral choices, even when it means sacrificing herself.

Bernard Rose’s 1988 film Paperhouse blurs the line between dream and reality, focusing on a bedridden young girl who finds herself inside her own drawing of a strange house when she sleeps. In this stark but fantastic world, she bonds with another sick child while her dreams burn and char into a horrible nightmarescape, reflecting the indelible scars left by a child’s death and by parental abuse and alcoholism.

A list of some of our favorite metahorror classics and modern gems. Not an exhaustive list, of course, but a good starting point if you need more metahorror in your life.

Spontaneous combines gallows humor and whiplashing tonal shifts to pile on emotional intensity, capturing two-plus decades of ongoing trauma on two generations of children the United States has failed to protect from mass shootings due to its own systemic incompetence and lack of political will. The film leaves you numb, reflecting the effect of personal and national trauma, as well as the necessity of overcoming it.

Craig Gillespie’s 2011 remake of Tom Holland’s 1985 meta-horror classic streamline's characters, cuts out the creepy sexualized treatment of Amy, and favors a more action-oriented approach over Holland’s self-aware campiness and references to horror movies of yore. But in buffing out the original’s messy strangeness, the remake loses some of the magic that made the original a beloved gem.

Rallying against many clichés that seemed built into the slasher genre at the time of its making, Cabin in the Woods was not only a rebuke of what the horror genre had become, but also a celebration of what it could be.

More than a quippy teen slasher brimming with meta-humor, Cabin is a teen slasher about making teen slashers. Leaning into filmmaking allegory and industry clichés, the film argues that the recycling of old ideas from the masters was unsustainable, that we needed to burn down the work of the Ancient Ones so that something new could rise from the ashes.

Let’s talk about the 1996 meta-horror mega-hit film Scream and how it’s meaning has changed post #metoo, now offering a critique of domineering misogyny and gaslighting, reflected in the film’s use of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ creepy, mysterious, broody, and catchy-as-hell “Red Right Hand.”

We wanted to bring you a list of good Pagan horror we didn’t get to talk about last month. But there was a problem. In our search for Pagan horror, we came across a lot of Satanic cults and witches, as well as some stories and creatures from old folktales, but relatively little in the way of what we would call Pagan horror. So instead, we’re going to tell you about some other great folk horror we came across.

Häxan has left behind a unique legacy, and lots of folks have written about it as an early film that blurred the lines between fact and fiction, reality and fantasy. It is also an essay, which is key to its integrity and artfulness. The Wrong Version of the film, recut, renamed a name we shall not name, and punched up with an out-of-place jazz score, scraps all that in favor of what feels like a deeply insensitive, drugged-out History Channel documentary.

In the wake of overwhelming tragedy and faced with the uncertainty of life beyond their four-year relationship, the main characters of director Ari Astor’s instant classic Midsommar (2017) reluctantly depart for the sunny hills of Hälsingland—a foreign town that serves the couple as a kind of limbo, testing each to see who they will become in the aftermath of a clearly failing relationship. Dani emerges with newfound purpose and identity, but her boyfriend Christian, loses himself at every turn, burning every social bridge that formed his identity until flames consume the little bit that’s left.

Happy Everyone’s Irish Day! Here are a few Irish horror movies we’ve watched recently. All the movies on this list were made by Irish filmmakers, all are set in Ireland, and all play off of fears that, in our American estimations (with some Irish heritage, which pretty much makes us experts, right?…), seem particularly Irish.