In Defense of Barbra: Night of the Living Dead

BEWARE SPOILERS

We go into every post assuming you’ve already watched the films being discussed.

While Night of the Living Dead (1968) is available on HBO Max and many other streaming sites as of this writing (7/07/2021), Night of the Living Dead (1990) is, unfortunately, not.

Last Saturday we went to Living Dead Weekend at the Monroeville Mall, where Dawn of the Dead (1978) was filmed, near the zombie capital of the world--that’s our hometown of Pittsburgh, PA by the way. Inspired by the event, today we’re talking about the film that defined the modern zombie in virtually all popular media since: George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968), co-written with John A. Russo.

All Romero’s Living Dead films, from Night of… to 2005’s Land of... capture something of when they were made. In 1968, that meant political and social turmoil surrounding Vietnam and Civil Rights. And even though Romero has said on record he never considered the racial significance of casting a Black man, Duane Jones, in the lead role as Ben in the ‘68 film (the same year Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated), plenty of others, including Jones himself, recognized the weight of it. Intended or not, Ben’s character is a key part of the film’s modern legacy as a groundbreaking and racially conscious masterpiece.

On the other side of the coin, though, is the poorly received original depiction of Barbra (Judith O’Dea), who Film School Rejects’ Jason Trussell calls "vacuous," a "frustrating impediment" who is “disengaged from the story as an obtuse wilting flower, glued to a couch, unwilling to lend a hand.” With Tom Savini’s 1990 remake of the film, the team (including Romero and Russo) set out to make a more feminist Barbara (Patricia Tallman). One with agency. One with an androgynous haircut. One who totes a gun. One who finally gets the “a” absent from her name in the original: BarbAra.

There’s something to be said about how this badass Barbara’s “feminist” qualities can all be seen as “masculine” traits--her gun savviness, her haircut, ditching the skirt for trousers. There’s an implied message here that, to overcome the terror around her, Barbara has to be more "manly." She has to be less traditionally “feminine” and more traditionally “masculine.”

Don’t get us wrong. This Barbara is also definitely a badass, and we love her for it--in the same way we love Alien’s Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver). But this particular character change, given how the original Barbra has been criticized, makes it seem like she was “useless” and got herself killed because she was just too “feminine.” Like she had to “butch” up to survive the remake.

On top of that, the remake sacrifices Ben’s legacy so that it can have its more “feminist,” more “useful,” more “likeable” Barbara. But we’re here to argue that the original Barbra’s reputation is undeserved. As frustrating as she might be to audiences, she represents a true-to-life type of character who should have more of a place in horror media. A type of character who, when they do appear in horror, deserves to live every once in a damn while.

Shock & Trauma

The 1968 version of Night of the Living Dead opens with Barbra and her brother Johnny (Russel Streiner) visiting their father’s grave so that they can lay a cross on it for the anniversary of his death. Johnny’s kind of a prick, and when Barbra kneels to pray at the gravesite, he scoffs, “Prayin’s for church.” Then he starts teasing her with the iconic, “They’re coming to get you, Barbra!” moments before an undead man in a suit attacks, killing Johnny and forcing Barbra to flee for her life.

It's a bit jarring at first. After spending the first several minutes viewing the world through Barbra’s perspective, once she finds refuge in the farmhouse, she spends the bulk of the film in shock, unable to act. The camera quickly shifts focus to our new, more capable hero Ben. Ben has dealt with these things long enough to know that they hate fire and aren't very strong. Ben has a gun. Ben talks like a man in command, telling Barbra to help board up the house, standing up to the malignant Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman), and rallying Tom (Keith Wayne), Judy (Judith Ridley), and Helen Cooper (Marilyn Eastman) to his side when Mr. Cooper acts like an idiot.

In short, Ben is the kind of character you want to follow in a movie about a zombie apocalypse. He's a badass with a strong will and wit to boot, alongside remarkable restraint and a whole lot of agency. He's a survivor. At least, you expect him to be. The Barbras of the world, on the other hand, you expect them to die. Quickly. And about both characters, you’d be wrong.

Well, in Barbra's case, half wrong. Despite her inaction through the bulk of the film, she survives longer than anyone except Ben. And even Ben, our more capable hero, dies.

Our favorite zombie movies, including the original Night of the Living Dead, are all about impending doom. Everyone you care about will die or become something terrible, from the most defenseless infant to the baddestass hero, and the people who survive will do so by betraying or sacrificing others. There are no real happy endings. Only holding actions. Eventually, society itself will crumble. (Unless someone finds a cure or whatever, but how often is that actually interesting? Well, maybe in The Cured (2017), but that's another article...)

And, in the face of such horror, if it were real, we’re not so sure there’d be a whole lot of Barbaras (with the other “a”) out there--nor so many Ricks and Alices (from The Walking Dead (2010) and Resident Evil (2002) respectively). In fact, we'd expect to see a hell of a lot more Barbras (of any gender identity). More people in shock, unable to act, traumatized by the death of a loved one, and falling to pieces along with the world around them.

Barb(a)ra

Here's the thing about traumatized Barbra: without her heroics near the end of the film, Ben almost certainly would not have survived the night. She finally pulls out of her catatonic state when the zombie horde is about to break through the house’s defenses and tear Helen Cooper to pieces. Bolting from the couch with a plank of wood, Barbra manages to hold them off long enough for Helen to escape.

She continues to hold off the horde (on her own!) over the following series of events: Harry Cooper succumbs to his gunshot wounds as his zombie daughter Karen (Kyra Schon) comes to eat him; Helen backs away from the door and stumbles down the cellar stairs into her zombie daughter’s murderous trowel; and Ben becomes occupied holding off more zombie breaches. When the horde overpowers Barbra, zombie Johnny breaks through. The sight of him throws her back into the shock she's just started to overcome. Once she recovers--much more quickly this time--there’s no escape.

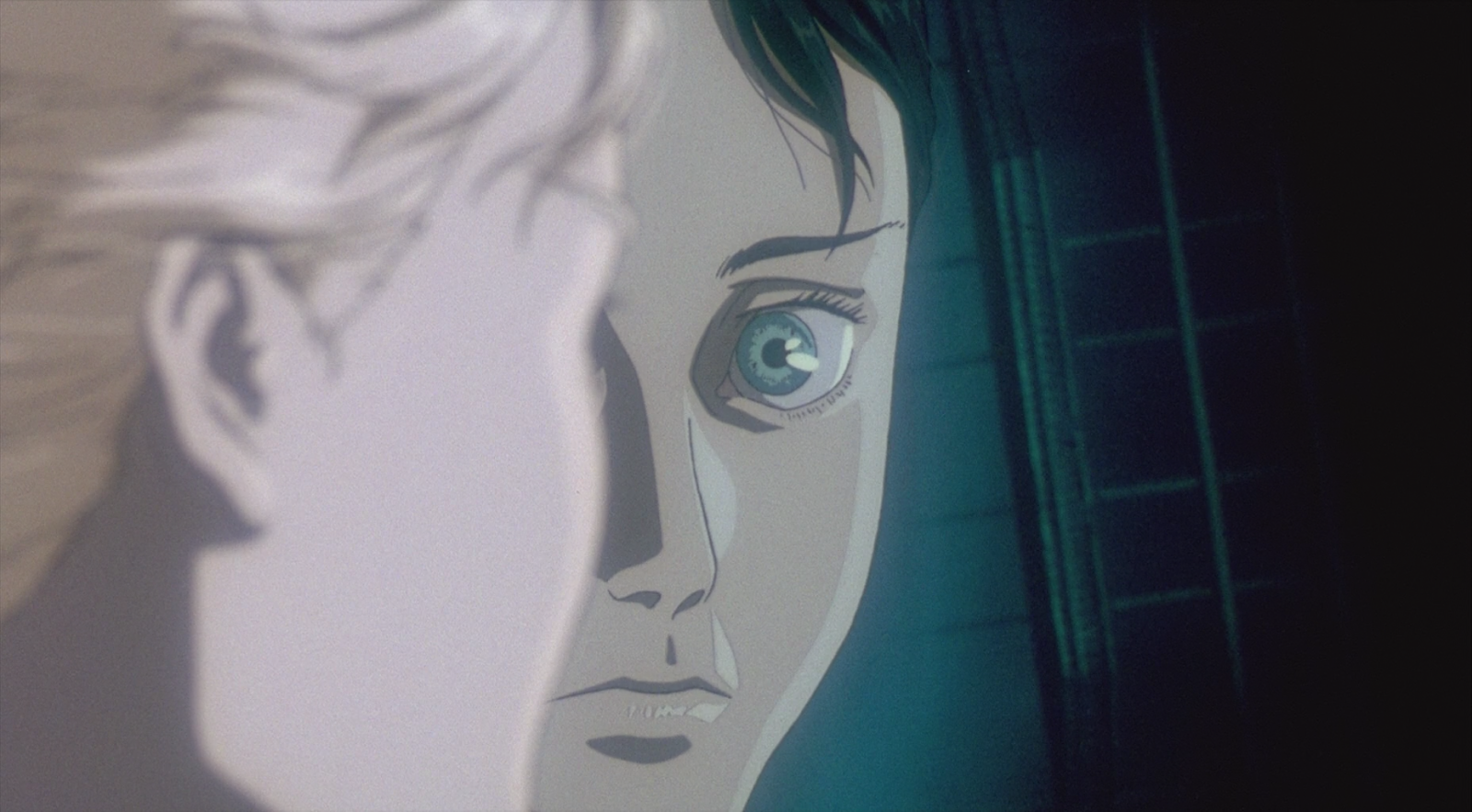

In the 1990 remake, Savini's Barbara sheds her appearance in the opening scene in favor of a more “masculine” identity. After her first zombie kill in the graveyard, she trades her skirt for a man's trousers (certainly a practical choice during a zombie apocalypse), dons a man's shirt, loses her glasses, and after getting over her initial shock rather quickly, becomes a hardened Ripley-esque badass.

And we love a Ripley-esque badass. We love Barbara's attitude and intelligence and level-headedness in the face of such trauma. We even love that glint in her eye toward the end of the film when she realizes, “They’re us. We’re them and they’re us,” and soon after shoots Cooper (Tom Towles) point-blank in the head. This Barbara certainly earns her place as a formidable “final girl.”

But to criticize the original Barbra, for being in a state of shock after her brother has been murdered in the midst of existential zombie-apocalyptic doom, seems cold-hearted at best.

Seriously, one of the last things her brother says to her before a zombie smashes his head on a gravestone and chases her until she “crashes” her car into a tree is, “They’re coming to get you, Barbra!” Then that same brother later comes back from the dead and pulls her into a swarm of hungry flesh-eaters who proceed to rip her apart, confirming all of her worst fears. If that character doesn’t get to be traumatized during the apocalypse, then who does?

To turn Barbra the traumatized into Barbara the survivor by making her more traditionally “masculine” seems like a misguided feminist revision--though, we admit, it’s a successful one. By which we mean, she's a great badass action hero. But transforming Barbra into Barbara in this particular way also seems to invalidate the original as “too feminine.”

And it robs us of a character type rarely explored with any depth or compassion. That version of Barbra, dismissed as hysterical, useless, and vapid (not to mention supposedly sexist in her portrayal), has more going on than she's given credit for. She feels real. She feels authentic to the story. And there's depth in her emotional response. She's a character who deserves to exist, especially because she's more like us than many of us would like to admit.

The Switcheroo

In the original, whether Romero meant it this way or not, casting Ben as a Black man and having his character outlive everyone else, only to be shot by a rural Pennsylvania zombie patrol that looks an awful lot like a lynch mob who then haul him out of the house on fishhooks and throw his definitely-not-a-zombie corpse on a zombie bonfire, was quite a statement about race in America in 1968: "When the zombie apocalypse comes, the bigots will take charge. They'll lynch zombies the way they used to lynch Black people. And they won't care much if they lynch a living Black man by mistake."

Even now, in 2021, that's quite a statement. But in 1990, Savini, Romero, and Russo decided to scrap that statement and swap it for this one, "When the zombies come, the bigots will take charge and form lynch mobs, and the rest of us will join them, because survival in this new world will mean accepting brutality and violence as a way of life, making us more terrifying than the zombies we kill." There's nothing inherently wrong with that message. In fact, it's kind of standard zombie commentary now because it continues to feel like a valid critique of humanity.

But, given how the film revises Barb(a)ra, that critique also seems to imply that to embrace a brutal way of life--to survive--means becoming more "masculine" and giving up essentially "feminine" parts of ourselves. There's that misguided brand of feminism again. And it comes at the cost of the original's sharp racial commentary.

It should be said that part of what makes Barbra seem so useless in the original is her contrast with Ben's character. As we've said, she’s in shock. She's mentally absent and physically inert throughout most of the film. She's non-responsive, despondent, and unhelpful.

Ben, on the other hand, is smart. He thinks and acts quickly. He's confident and capable. Moreover, his outbursts of anger are all understandable--he's as frustrated with Barbra as the audience is, he knows Cooper is a bigot who's going to get everyone killed, and he's the only outwardly smart, thoughtful, quick-acting, confident, and capable person in this whole damned zombie apocalypse. Who wouldn't get angry?

And Duane Jones' performance adds further depth to the character. Despite the circumstances, Ben shows wisdom and restraint. He apologizes to Barbra for striking her and becomes her fiercest advocate. He makes peace with Cooper as best and as long as he can to try to get everyone through the night.

Looming over Ben's restraint is the stereotype of the angry Black man, which at times he seems actively trying to avoid, especially in his interactions with Barbra. In short, Ben is an extremely engaging character with real emotional depth. Casting a Black man to play a lead as likeable and smart and capable and restrained as Ben in 1968 meant something.

None of that changes in the remake, and Tony Todd is phenomenal, showing similar depth of character with his own approach to the role.

What does change is the ending.

In the original, after everyone else is killed, Ben barricades himself in the basement, where he finds and kills the undead Coopers. While zombies overrun the rest of the house, Ben makes it through the night. Then, in what is the film’s fastest, most undramatically presented, but most horrifying death, he's shot in the head by a member of the posse who, it would seem, couldn't possibly have mistaken him for a zombie, this Black man, standing upright and peering cautiously through a boarded window over the sight of his gun. "Okay, he's dead. Let's go get him.” “That's another one for the fire," a second man says.

In 1990, badass survivor Barbara leaves the house to find help. She meets the posse, whose lynch mob resemblance has only increased in the remake. And in this version, when Ben and Cooper fight in a ridiculously lengthy shoot-out, it’s Ben who’s fatally wounded. Cooper escapes into the attic, leaving him for dead, and Ben barricades himself in the basement soon after. When Barbara brings the posse to the house in the morning, they open the basement door, and zombie Ben shuffles out. Upset at the sight of her dead ally, Barbara leaves the room as the two members of the posse who followed her into the house unceremoniously shoot zombie Ben in the head.

Cooper, who’s heard the commotion of possible rescue from the attic, makes his way down the stairs and reaches out to Barbara, huffing with relief, "You came back!" She looks at Cooper a moment before lifting her gun with a barely concealed smirk and shooting him in the head. When the men come in and ask what happened, she echoes the original film: "There's another one for the fire." The men shrug.

Cooper's death in both films is satisfying. He's a self-interested, sociopathic bigot perfectly ready to sacrifice someone else's life if it benefits him. So, when he gets killed because of his own bigotry, selfishness, and cowardice in the original, you feel like he deserves it. In the remake, Cooper's even more of an asshole, but rather than being killed as a direct result of his own flaws, badass survivor Barbara condemns him to a swift execution for imperiling everyone else’s survival and for Ben’s death, which she rightly assumes is Cooper's fault. It's satisfying in a vigilante justice way, and it's interesting in that it implicates Barbara in her whole "We're them, and they're us" epiphany.

But all of that comes at the expense of Ben. The injustice of his death in the original feels like biting and horrific social commentary, and it's somehow softened by the (albeit uncomforting) idea that everyone dies. In the remake, though, his death feels narratively insulting. He still gets shot in the head by the zombie lynch mob, but this time he really is a zombie, so the racial critique is gone. Worse still, bigoted Cooper outlives him.

On top of that, even though Barbara survives (which is great), Ben’s death makes it feel like the remake has sacrificed the original's Black hero so that a white woman can live.

Justice for Ben & the Barb(a)ras

In short, the remake does the original Ben a terrible narrative injustice for the sake of a surprise ending, and it replaces sharp racial commentary with what feels like a misguided brand of feminism.

It's not unreasonable to want to revise traumatized Barbra to make her more compelling onscreen and give her more agency. We can't deny that she's frustrating. But the believability of her reaction to personal tragedy and impending doom is a large part of what makes the original Night of the Living Dead so horrifying.

And as we’ve said, we love badass survivor Barbara. We can't deny that she's magnetic and fun to watch, and it's just good, in a movie from 1990, to see a smart, capable female hero. But having her outright replace an unfairly maligned character (who embodies an underrepresented emotional response in apocalyptic horror) feels like undeserved dismissal that effectively invalidates Barbra's very realistic and understandable shock and trauma.

So we're writing in defense of Barbra, but we're also writing with love for Barbara. Both are valid characters who deserve to exist in the same universe, but you know, with different names probably. 1990 Ben, on the other hand, just plain deserves better.

It's not hard to imagine a version of Night of the Living Dead in which Barbra has her nervous breakdown, Barbara is a separate character named Amy or something, Ben overcomes Cooper, and they all make it out alive, except Cooper who gets eaten by his zombie wife and kid because he’s a loathsome character who deserves a horrible, cannibalistic death. But to do all of those characters their proper justice, you have to throw out the impending and inevitable doom that serves as the foundation of the best zombie stories. Because if all your favorite characters live, then what was really at stake?

And in that case, maybe the issue isn't just the replacing of traumatized Barbra with badass survivor Barbara. Maybe it's not Ben's narratively unjust death either. Maybe the real root of the problem is letting any of the main characters survive at all.

Maybe that’s what made the original so horrifically great in the first place.