The Ticking of Clocks

BEWARE SPOILERS

We go into every Dissection assuming you’ve already watched the films being discussed. In other words, we’re about to spoil the hell out of The House (2022), which you can watch on Netflix as of this writing, February 26, 2022.

Recently, we made a little announcement that we were postponing the week's article because I'd had an epiphany while writing my Judgment on Netlix's 2022 film The House and realized I didn't want to write a Judgment. I wanted to write a Dissection. I said you'd have to wait another week, but that you'd get a better article in exchange. Well, a week and a few days later (or two full weeks later if you're not one of our generous Patreon supporters), I have that article for you. And it's long for what we normally put out. Almost 4,500 words, which is 50% longer than our usual Dissections. So it's late, but it's longer, and it's better. Balances out okay, right? Plus, it's the start of a new Dissection series.

Here at the Other Folk homestead, we have a soft spot for animation. Stop motion, 3D, traditional, what-have-you. We love Studio Ghibli and Don Bluth and Cartoon Saloon. And yeah, Pixar too. Sometimes, even Disney.

What? Don’t look at us like that. We’re not just horror fans, you know. We have other interests too. 1970s punk and glam rock, for example. And tabletop roleplaying games. Also, long road trips and doting on our ridiculously neurotic part-Siamese cat.

Anyway, animation is another thing we like, and we haven’t really talked about it here before, even though there’s an incredible amount of excellent animated horror out there, from family-friendly mainstream hits like Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) and Corpse Bride (2005) to the anime classic Akira (1988) to the psychedelic and child-traumatizing Watership Down (1978) to possibly the first horror movie I ever saw, The Secret of NIMH (1982).

In fact, the research we’ve done so far suggests a whole world of animated horror whose surface we’ve hardly scratched. So we’re gonna remedy that with a new series of Dissections completely focused on animated horror, starting today. For this first entry, we’re cutting open dolls and digging through felt flesh and cottony viscera for art things.

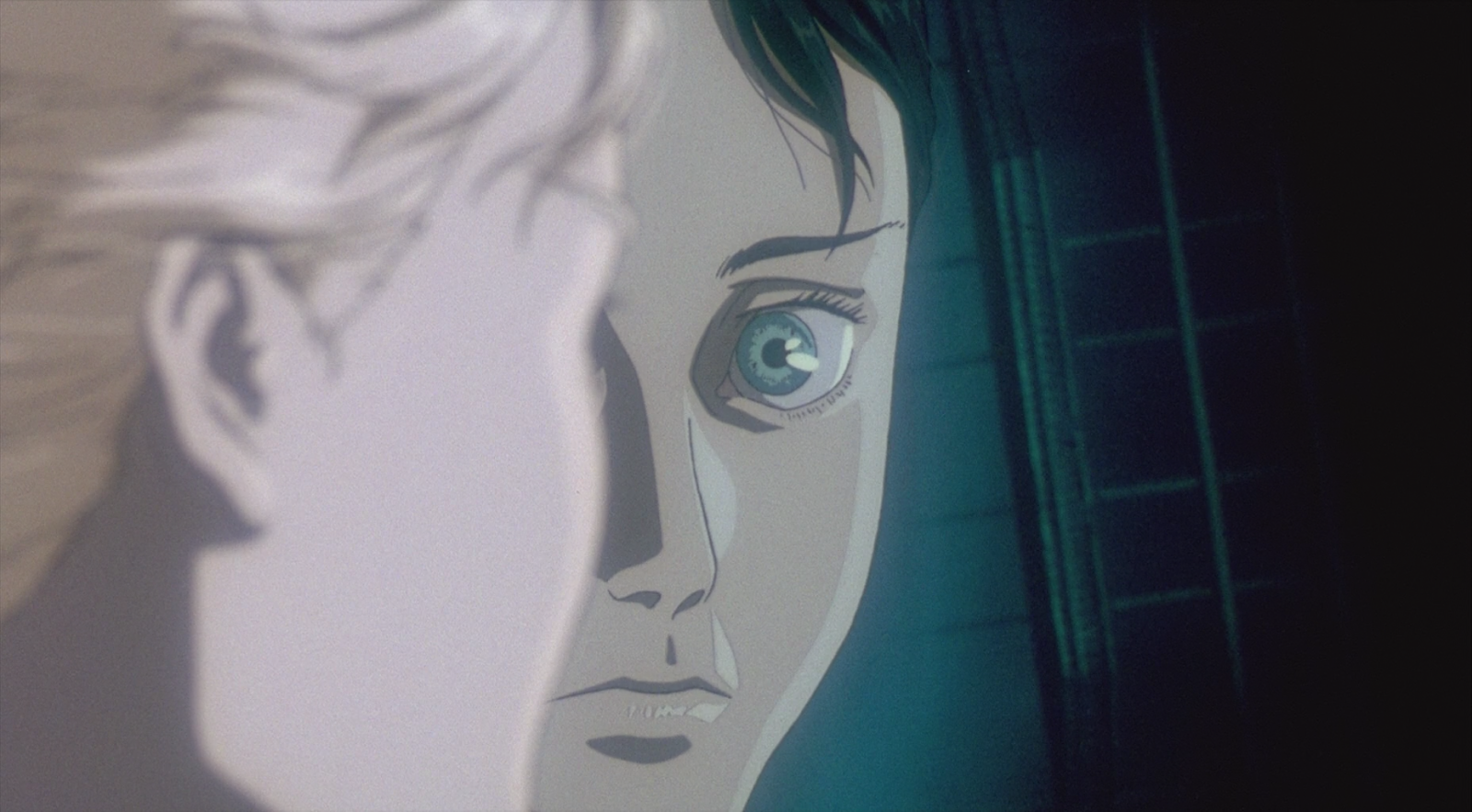

Enda Walsh’s recently released collection of animated horror, The House (2022), showcases three short films set in different worlds, at different times, but they all take place in the same house. Each film in The House has its own distinct and striking visual style. The meticulously arranged shots work to great effect, rendering images at times that look like they could have been lifted from classic horror films like 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby (which we wrote about sort of recently), 1982’s Creepshow, and 1973’s The Wicker Man (on which we wrote our first ever Dissection).

If you’re not paying careful attention, you might think the house is the only thing that connects the three stories, but taken together, they tell a story built more out of themes and ideas than plot and individual characters. All three shorts develop shared and interrelated themes: Industrialization, materialism, greed, loss of home, and individual weakness in the face of great disaster. In sum, those themes—when set across these three periods of not-too-distant past, present, and not-too-distant future—tell a narrative of environmental horror brought on by modern human greed, materialism, and self-delusion about the doom we’ve created.

Titles & Ticking Clocks

I know lots of folks have lots of feelings about poetry, including anxiety, frustration, and indifference. I get that. But I’m going to briefly talk poetry here, partly for reasons specific to The House that I’ll lay out in a minute, but more because knowing a little something about poetry helps you think about other art, including film.

Here’s why: Humans have written in verse much longer than we’ve written in prose—not to mention oral poetry, which we’ve been doing much, much longer than we’ve been writing anything. Poetic and musical devices like rhyme schemes and alliteration and stomping and clapping and beating on whatever we found that made a satisfying sound—it all helped us remember stories we hadn’t yet figured out how to write down.

So poetry is really, really old. Almost as old and deep a part of our cultural DNA as music. That makes poetry the basic building block of literature, including novels, stories, essays, stageplays, film scripts—basically anything that involves words.

Here’s a story from back in my teaching days. Early in an intro to literature course, my college freshmen read Louise Glück’s famous poem, “The Wild Iris.” I asked them to read it in class three times, once quietly to themselves, again as I read it out loud, and one more time to themselves. Then they discussed in groups what they thought the poem was about.

It was early in the semester. Baby steps. The idea was to get them past the gist of the poem so they’d pay more attention to individual words, lines, and sentences, the smaller bits that add up to the bigger bits that together equal the poem.

Right away, they said the poem’s morbid, which is true enough. Thematically, the poem is definitely about death. But they were missing the literal part, skipping over what actually happens in the story that the poem tells, and as a result, they were missing the other half of what it’s thematically about.

I asked them to look again at the title, “The Wild Iris.” A few students, even if they didn’t quite get it, realized the rough shape of what they were missing. One of them asked, “What’s a wild iris?” Another explained, it’s a flower, and she thought she remembered it’s a perennial flower, too—meaning, even though it dies at the end of each season, it regrows the next without being replanted. (She was right. Irises are perennials.) The poem, she realized as she was explaining, is as much about birth and rebirth as it is about death.

I had a similar experience with The House. I was looking so closely at the individual shorts that I couldn’t see the most obvious clue about what connects them. Their titles, taken together, form a three-line poem:

And heard within, a lie is spun.

Then lost is truth that can’t be won.

Listen again and seek the sun.

The poem goes a long way in uniting the three shorts, first because the poem is a thing in itself, made from the titles of the shorts. But there’s also the triplet rhyme scheme and the sing-songy quality working as additional glue to hold it all together—as signposts telling readers that the short films go together.

(That sing-songy quality, by the way, comes from the fact that each line has eight alternately stressed and unstressed syllables: “And heard within, a lie is spun.” In academic jargon, they’re octosyllabic lines made of iambs. Makes it sound old and folksy.)

And then there’s the matter of the clocks. As you may have caught yourself, the title screen for each part shows a clock (of sorts). Part I’s animated clock starts at 11:59 and—so quick you could easily miss it—ticks to midnight. Technically, it could be noon, but the digital clock in the title screen for Part II flips from 5:59am to 6:00am, and the sundial that begins Part III is nearing sunset. The stories are presented as if they take place on the same day, even though we know they don’t, to reinforce the less obvious connections between them.

In other words, even though each short is set in a different world, at a different time, with different and unrelated characters, the structure of The House—how the narratives are organized and presented—insists they’re part of the same story.

That story is off to the side. You don’t even need to see it to enjoy the movie. But it’s there, and by my reading, it’s all about climate change as the inevitable result of expanded industrialization, consumerism, and materialism from the early 1900s to the near future. Even the collection’s vaguely optimistic conclusion is haunted by deep fears of the unknown journey that lies ahead in the face of a world transformed by rising floodwaters.

How did I get there, you ask? Well, it all starts with the titles and plays out in the plot of each short, as the characters face unavoidable creeping doom brought on by the actions of others and must either flee or be consumed by the forces overtaking their homes and their worlds.

Part I sets a thematic conflict, a lie of materialism and greed that consumes Mabel’s parents. That lie of materialism sets up the self-delusion and realization of the Developer (Jarvis Cocker) in Part II, and it resolves in Part III’s Rosa (Susan Wokoma), who’s also delusional, as she accepts reality and moves on from what she (and the world) have lost. Taken in the context of climate change, those thematic developments tell a story deeply critical of humanity.

“Part i. And heard within, a lie is spun.”

Directed by Emma de Swaef and Marc James Roels, Part I blends whimsy, bleakness, and grotesquery in a way that feels like one of those excellent horror-themed episodes of Doctor Who, except the Doctor doesn’t show up to save the day, and instead a little girl and her infant sister Isobel’s parents get turned into furniture, and their whole lives burn to the ground, and they escape from the house as orphans, and the little girl now has to raise her baby sister on her own. The end.

(Paragraphs like that one are why we like spoilers so much.)

Like I said before, titles mean things, so I’m going to start with this one: “And heard within a lie is spun.” First, what’s the lie? Heard within what or who? Who does the hearing, and who does the spinning of the lie? Why do we begin with “And”? Why is it heard from “within” and not “without” or “throughout” or “everywhere” or something more specific?

That’s what looking at the title gives us—lots of questions. Most of the answers live in the rest of the film, except the part about beginning with “And.” That part, to me, says that even though this is the beginning of the story, it’s part of a bigger narrative. That part of the title places the story in a broader history.

As for what history and which part of it, the short begins with Mabel (Mia Goth), a young girl in a British home. She and her parents, Raymond (Matthew Goode) and Penelope (Claudie Blakley), wear clothing that looks like it could be from the late 1800s or early 1900s, and there are no electric light fixtures in the home. In fact, the family’s first encounter with electricity seems to be when they move into the house designed and given to them by Van Schoonbeek (Barnaby Pilling).

I won’t get too deep in the weeds on this, since it’s all pretty easily searchable, but the point about electricity places us pretty well in the 1920s or early ‘30s, the period after the Second Industrial Revolution and following World War I, when the inventions and discoveries of the past several decades were becoming widely available to the public.

So there’s the historical context the title’s “And” is telling us to notice. What about the “lie”? It’s the most glaring word in the title. Nouns have a way of standing out like that. Plot-wise, the main action in the story is that the family is gifted this house by the weird, rich architect Van Schoonbeek who, we soon suspect, has lied for nefarious purposes.

Early on in the film, having been berated by his Great Aunt Eleanor (Stephanie Cole) and mocked by his Uncle Georgie (Joshua McGuire) and other relatives for being a poor drunk just like his father, Raymond—as anyone who understands addiction and story tropes could predict—gets drunk and goes on a good old-fashioned stumbling through the woods. He comes across a mysterious carriage, in which a thinly obscured Van Schoonbeek tells him something we can’t hear.

Right after that, he returns home with a gluttonous hunger, raving about how “everything’s changed.” The next morning, someone named Mr. Thomas (Mark Heap) comes to the door to officially say what, it seems, Van Schoonbeek suggested to Raymond the night before, an offer to build them a home as a gift, on the condition that they abandon their current home and belongings. We find out later, Van Schoonbeek hired Mr. Thomas, an actor, to convince the family to move into the house and keep them there until they’re eventually furniturized.

But as nefarious as turning a family into furniture is, the story about the house being a gift and the things Mr. Thomas says to them don’t seem to be the lie mentioned in the title. That lie is “heard within” by Raymond and Penelope. The audience doesn’t hear it directly, but we know it leads each of them to greed, gluttony, vanity, obsession with the material luxuries in the House: Fine fabrics, elaborate meals, electric lighting. Not to mention the custom furniture designed to match Van Schoonbeek’s architectural artistic vision.

It’s a lie connected to materialism, class shame, and loss of the individual—all major concerns of Western thought in the years this first short film is set, soon after the Second Industrial Revolution and leading into World Wars I and II, including in the minds and works of thinkers and artists ranging from philosopher Walter Benjamin and playwright Samuel Beckett to artists like Pablo Picasso and the world’s first international film star, Charlie Chaplin.

Raymond and Penelope hear the lie from within, having internalized Great Aunt Eleanor’s criticisms, Van Schoonbeek’s temptations, and Mr. Thomas’ tacit judgments: They must have more things, newer things, things that will show them to be better, that will make them better than the lazy poor folk they are. This lie of materialism, greed, and status brings them into the House, turns them into furniture, and orphans their children.

“Part ii. Then lost is truth that can’t be won.”

After Part I ends in tragedy, Part II, directed by Niki Lindroth, begins sometime around our modern day. In some ways, this world is dingier than the first. It’s inhabited by rats, rather than the old-timey human dolls of Part I. The opening shot is trained on a pile of garbage outside the House. But parts of it are polished up—the marble countertops and steamed carpets and fancy LED lighting system.

When we meet the protagonist of this new story, credited as Developer, he’s trying to fix up the now-dilapidated House so he can flip it to someone before they notice its problems. He’s on the phone, fighting with a representative at a contracting company, complaining that he had to send their workers home because they were incompetent.

The guy on the other end of the line calms him down, but the Developer’s day doesn’t get any better. While he’s working to get the place ready for an open house, he discovers a bug infestation. Without any protective gear, he bombs the place with pesticides. Then, exhausted, having breathed in clouds of pesticide, he falls asleep on the kitchen floor, surrounded by dead bugs. The way he’s curled echoes the shapes of the dead bugs around him.

All of this—the garbage, the rats, the flipping of a junk house, the bug infestation, and more stuff I’ll get to in a minute—adds up to Part II’s title.

If the lie of Part I is about materialism, greed, and status, then the lost truth of Part II is about our place in the world, what we do to it in the manufacture of so many things. Not to mention what we do to each other. The Developer is constantly on the phone fighting with customer service representatives, lying to business associates, and as we find out later, harassing his dentist. Even if he appears reasonable in some cases—as when he complains to a grocery delivery service for having delivered the wrong groceries—it’s all so he can win a sale and flip a junk house on an unsuspecting buyer.

The “truth” of Part II can’t be “won” because “winning” is what got us here in the first place. Our need for more and newer things leads to growing piles of waste until we find ourselves trudging through a world littered with the old and discarded. We build homes that displace other creatures, and then we work relentlessly to fight off infestations of pests and vermin. The truth that Part II wants us to see is that we are the pests; we are the vermin bringing rot and destruction to the world we call home.

After the Developer mops up the dead bugs and figures out his grocery situation, people start arriving for the open house. The sequence that follows shows the shoddiness of his renovations, as well as the plague-like way the guests pour through the House, leaving trails of filthy footprints, breaking fixtures without saying anything. One kid smears a strawberry ice cream cone all over an aquarium and throws the rest of it into the tank. The camera keeps returning to images of the fish swimming around in the filthy pink water until it dies.

The disastrous showing culminates with the Developer delivering a whole lot of sales-y bullshit to people who are starting to buy it until the smart lights begin uncontrollably strobing red, green, and blue.

Just as he’s sure he’s blown any potential sales, a pair of creatures credited as Odd Couple Wife (Yvonne Lombard) and Odd Couple Husband (Sven Wollter) approach him to say, in monstrous voices, “We are very interested in this house.”

The Developer starts catering to their every demand. He lets them sit and watch TV. (They find one program about a mold infestation very amusing). They bathe and nap and dine in the House. They invite family to stay. And the Developer lets them because he believes they’re planning to buy.

The reality, viewers figure out faster than the Developer, is that the Odd Couple are freeloaders, stringing him along, feeding off of his desperation.

Meanwhile, the bug infestation has gone from disgusting to Biblical. The Developer’s losing his mind fighting them off while trying and failing to get the Odd Couple to move forward on the House. At the same time, he keeps lying to a business associate over the phone, claiming he’s deep in negotiations, that they’re even on their way to the bank to work out loans.

Finally, he can’t take it anymore. The Developer tells his associate the truth, that the Odd Couple are stringing him along. Then he explodes in a fit of rage at the Odd Couple, who find his anger very amusing and laugh while he struggles with a container of insecticide he intends to throw all over them. He drops the container and takes a cloud of it to his face, which knocks him out and sends him to the hospital.

When he wakes up, the Odd Couple have come to visit. They say it’s time to take him home, and the Developer, it seems, has lost his will to resist. They take him to the House, and as he steps into the foyer, we see the Odd Couple’s family standing and applauding his return. The House is utterly overrun with the family of vermin eating and destroying everything. It ends on a shot of the Developer, now naked and on all fours, bursting through the oven, looking around, and then scuttling back through the tunnel he came from. Part II ends as the camera follows him into the darkness.

We’re seeing the Developer, in this final moment, as his true self. Like the Odd Couple’s family swarming the House, like the bugs infesting it before them, like the guests trampling filth and throwing ice cream in a fish tank, the Developer is nothing more than vermin. He and the other rats of this world have brought it to its filthy state, in which they wallow.

You don’t have to squint too hard to see this as criticism of modern greed, materialism, and waste, not to mention our self-delusion in not seeing beyond the fine fabrics and marble counters. It’s our old and discarded possessions that litter the Earth. It’s our materialism and consumption that lead to a world in which we demand and impose upon others as they demand and impose upon us. In this context, winning through the possession of new things and the discarding of the old, means continuing to destroy our shared home.

Part II isn’t about the Developer being turned into a rat. He’s a rat from the beginning. The story is about the terrible revelation that he and the other rat-people of the world are what they are, an infestation.

“Part iii. Listen again and seek the sun.”

So Part I introduces a lie of materialism and class status that the developed world internalized after the Second Industrial Revolution.

And Part II argues that this lie turned us into an infestation of pollution and misery who, now in the Digital Age, bring madness and confusion to our own lives.

Part III, directed by Paloma Baeza, is less condemning of its protagonist’s self-delusion. The sundial replacing the analog and digital clocks of Parts I and II for this new title card approaches sundown, and the film opens on a bleak shot of a village overtaken by rising waters and strange mists. It’s a post-apocalyptic world, now inhabited by cat-people, destroyed by a changing climate.

Rosa is the House’s owner now. She rents out two of its rooms to people she thinks of as friends, but also as freeloaders. For some time now, they’ve been paying her in fish and crystals, but she continues to demand proper money. They tell her everyone’s left, money’s no use, but she doesn’t want to hear it. She goes on about all the work she’s doing to improve the house and yells at them for not paying her any rent to help her make repairs.

Rosa’s energy and dedication have a strange effect. She sort of convinces you—or at least she convinced me at times—that she’s right to expect rent in a post-apocalyptic world where it seems money wouldn’t have much value. She comes off as a really kind and hard-working landowner. The first scene finds her putting up new wallpaper, which immediately peels down and falls over as the mists gather. We also learn that she’s managed to take care of the plumbing, fixing it every time her tenants say the water's brown again, and we see her diligently working to improve the House she rents out. She’s kind to her non-paying tenants too, ultimately accepting their non-money, even if she gives them an earful for it.

Of course, then you think for a second, and you realize how ridiculous it is for her to expect money. The horror of Part III is quieter. It lives in Rosa’s obvious self-delusion, the absurdity that arises from it, and her slow path to acceptance. Her conversations with her tenants feel reasonable because they’re rooted in the logic of the real world, the one we live in. But the conversations are all upside down and obscured. With each one, you have to “Listen again,” as the title says, to remember that she’s completely delusional and imposing her madness of nostalgia on everyone around her.

The story she tells herself—that new tenants will come, “better people,” people with “real money,” if only she makes these repairs on her isolated island of a home—is tragic in its detachment from reality. As the waters rise around her, as her tenants Elias (Will Sharpe) and Jen (Helena Bonham Carter) try to get her to accept the truth, Rosa refuses to let go of the past, of her belief in this lost world of things and now useless money as shared reality. She suffers from what you could call absurdist nostalgia horror.

Jen, a woo-woo hippie character who pays her rent in crystals, says her “spirit partner” Cosmos (Paul Kaye), with whom she communes on the astral plane, will soon come. He arrives on a raft surrounded by mist, announced by the sound of his throat singing, a skill he says he picked up in Tibet.

Sensing that Cosmos has come to stay, Rosa says she should charge him rent. Cosmos replies, “What is money but coin and note?” Again, that strange trick happens, in which you’d be forgiven for thinking the guy’s an idiot or a sleeze and Rosa’s wholly in the right. But then you quickly realize what he’s saying, following the collapse of civilization, is in fact an obvious truth that Rosa refuses to accept.

They come to an agreement when Cosmos mentions that he moves “in an ocean of bartering,” trading his carpentry for food and lodging. She immediately agrees to let him stay if he’ll help her fix the house, but his understanding of what it means to “fix the house” is quite different. He tears up floorboards to build Elias a boat, and he comes up with a “nonaggressive solution to the plumbing,” performing a ritual and making changes to the house that don’t become clear until later, when we find out he’s converted it into a boat.

Rosa is, of course, outraged about the ripped up floorboards and demands Elias take apart the boat he’s planning to use to escape the flooding. He refuses and tries to get her to see reality, but she storms off in anger. Worse, she misses him when he sets sail the next morning.

The story climaxes when Cosmos and Jen work together to surround Rosa in the strange mists. While enveloped in them, she has a vision of Elias and Jen sitting on the couch, but they appear monstrous and terrifying. She starts to see that she’s turned her tenants into symbols of the past, clinging to them, holding them and herself back.

In her vision, they laugh maniacally at something on the television. She sees herself on the couch, joining in on the mania, swallowed in this mist of the past. Then her friends disappear, and she sees herself wallowing in the mist alone. If this short fits into this loose idea of nostalgia horror I cooked up a few paragraphs ago, this is the moment her nostalgia reveals itself to her as horrific.

This hallucination of her friends transformed into monsters finally gets her to the truth, that the world as she knew it is no more, that she has to leave it behind and move on, into the unknown that the future holds.

The title of Part III, “Listen again and seek the sun” calls on Rosa—who is a stand-in for people blind to the realities of climate change—to see through those obscuring mists, the lie of materialism and status from within. It tells her to seek the sun, the light of truth. It tells her to accept that the world she knew is gone, that her money is worthless, as is those of her imaginary tenants who she believes will pay her in coin and paper note, which she cannot spend or eat or use for shelter.

In the end, Rosa must accept that she can’t win that world back with elbow grease and better tenants. Instead, the title card, Elias, Jen, Cosmos, and the world itself tell her she must try again to build a better world.