Grotesque Comedy, Part 1: The Stepford Wives

BEWARE SPOILERS

We go into every post assuming you’ve already watched the films (or read the book) being discussed.

The Stepford Wives (1975) is available on tubi as of this writing (6/13/2021). The 2004 remake isn’t available at the moment. (But that’s okay. You don’t need to see it. And yeah, we’re still gonna tell you what happens. Because, like sauerkraut or bleu cheese, these things are better spoiled.)

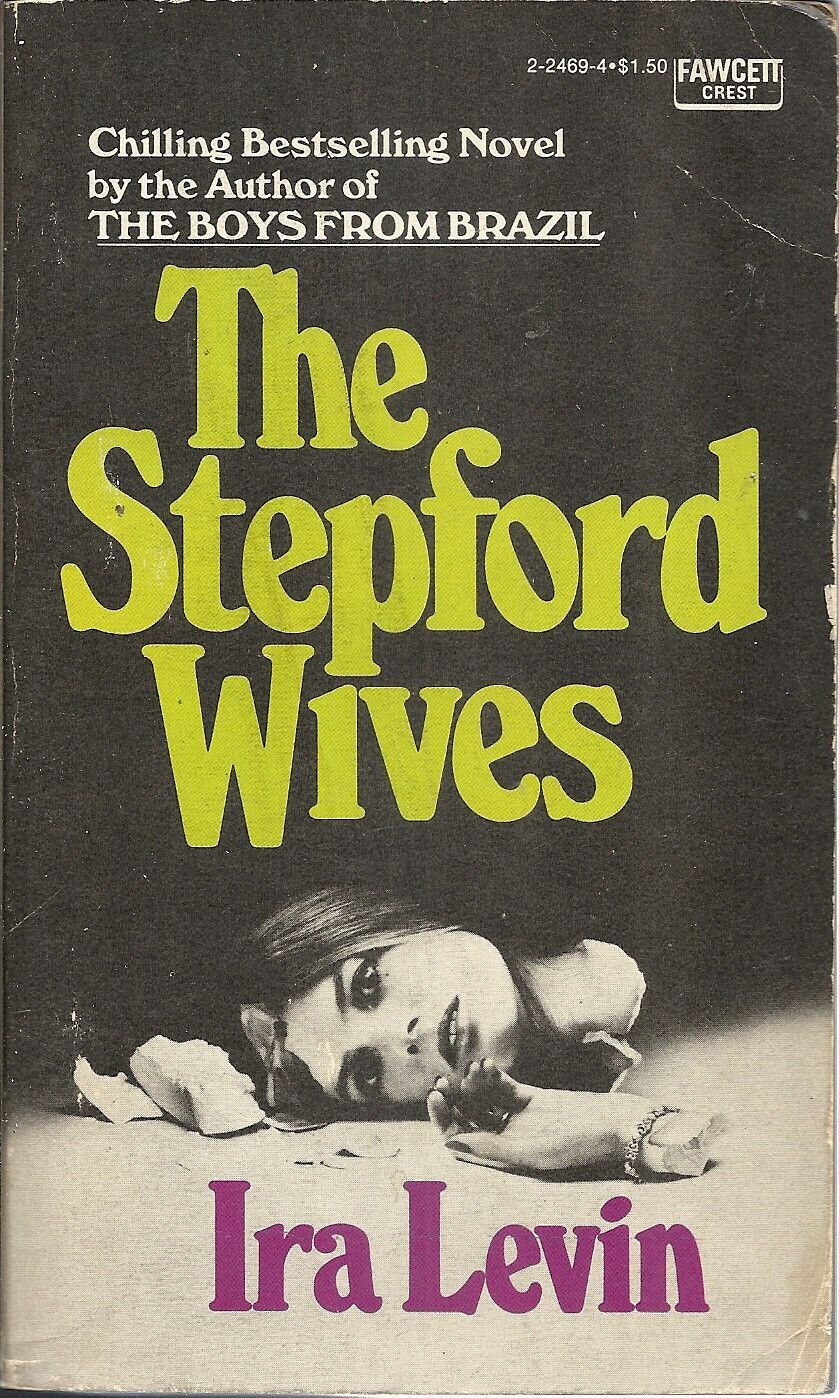

We’re kicking off a two-part dive into the legacy of The Stepford Wives: Ira Levin’s 1972 novel and the films it inspired. Today, we’re starting with a look at the 1975 social thriller classic and the regrettable 2004 comedy of the same name. At its core, Levin’s novel is a work of satire, a genre often misread and misunderstood.

Just a quick distinction here between satire, parody, and farce: when I say satire, I mean, stuff with teeth, biting social critique. For the most part, I don’t think of Monty Python, Saturday Night Live, or Pride and Prejudice and Zombies as satire, so much as parody and farce, with the occasional bit of sharp-toothed satire sprinkled in. They might be mocking aspects of culture and society, they might poke fun at a politician or a celebrity, but they’re not trying to draw blood, and often the person or group being mocked is in on the fun.

Satire, though, is harsh. It’s meant to make you uncomfortable. And it’s meant to get you thinking.

Take Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” the satirical essay that’s basically become The (Western) Cultural Touchstone for defining satire. Swift “argues,” the best solution to crippling poverty in eighteenth century Ireland is to sell Irish children to the British as … food:

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.

The essay’s serious tone highlights the absurd horror of such a proposal, but it also brings to mind what was then a common attitude among the Irish, that the British were eating the Irish, consuming every bit of national income through taxation and other means of economic cannibalism. Swift was saying the same thing, but in a far more public and horrifying way. The essay’s meaning lies in the fusion of horror and deadpan comedy, not in the “argument” Swift makes.

Satire is what happens when you marry comedy with the grotesque. That’s what makes Levin’s novel so lasting and powerful. It’s also what both film adaptations are missing. Director Bryan Forbes’ 1975 social thriller focuses on the horror of Stepford, but it suppresses the comedy. And Frank Oz’ unfortunate 2004 remake entirely scraps the horror in favor of absurd comedy, leading (if unintentionally) to a mockery of Levin’s feminism.

Stepford, 1972

Inspired by Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and fellow second-wave feminist Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Levin satirizes the mid-century, middle-class, white American attitude that keeping house, raising kids, and meeting their husbands’ sexual fantasies is how women find fulfillment. The Stepford Wives is about the grotesqueness of a world that suppresses women’s creativity, intellect, and independence.

In the novel, Joanna Eberhart, a self-proclaimed semi-professional photographer “interested in politics and in the Women’s Liberation movement,” moves with her husband Walter and their children from the “alive” city to Stepford, the kind of sleepy, seemingly idyllic suburb with a terrible underbelly we came to know and fear in ‘80s and ‘90s film and TV like Pleasantville (1990), The ‘Burbs (1989), and the underappreciated 1991-92 NBC series Eerie, Indiana. This one’s in Connecticut. Joanna must discover the truth behind the “town the world forgot” before her time runs out.

The Stepford wives have no intellectual pursuits or creative interests, consumed by maintaining their homes, raising their kids, and serving their husbands. They don’t go out or socialize, and they happily wax their floors at night while their husbands get drunk, play cards, and make murderous plans to replace their wives with subordinate, passive, and wholly devoted sex-fantasy robot wives at the Men’s Association.

Levin’s nuanced satire highlights a particular kind of sexism and male entitlement with a careful blend of comedy and horror. But the book demands a reader who reads between the lines. There’s been a strain of criticism mistaking his subtlety for ambiguity, as if the answers are never laid bare, but Levin meticulously sets all of it up. He’s just never explicit.

Even worse, some have argued that maybe Joanna, the protagonist who’s husband gaslit her for four months and who watches her two friends get body snatched after a weekend away (with their husbands) before her own weekend finally comes, hasn’t been murdered and replaced by a Stepford robot at all. She’s just suddenly decided she actually is happier as a housewife and wasn’t much good at photography anyway.

I just want to clear a couple things up. First, the book is not at all ambiguous about the fact that Joanna is a talented photographer who makes money selling her work.

Second, this reading ignores Joanna’s last moments. The men convince (gaslight) her into visiting Bobbie to see for herself that her friend hasn’t been replaced by a robot by proving that Bobbie still bleeds. She realizes soon after arriving that the music is blaring upstairs, “in case she screams.” Bobbie beckons Joanna closer, wielding a kitchen knife. “The men are waiting,” Bobbie says.

In her last moments, Joanna marvels at how real this new version of Bobbie looks. After months of paranoia and gaslighting, she truly doubts herself. But this isn’t some sudden realization for Joanna. It’s the horror of the book: Joanna’s husband, the other men, and even the other housewives have succeeded in making her feel insane before she’s murdered and replaced by a Joanna-shaped housewife sex-bot. That is, unambiguously, the last we see of the Joanna we know.

It’s horrifying and absurd at the same time. The premise is ridiculous on its face, but it also reads like a grotesque parable. That’s why it’s good. Don’t forget that.

Stepford, 1975

Bryan Forbes’ 1975 film adaptation, what today we would call a social thriller, emphasizes the terror and downplays the humor. The film opens with the family loading the last few moving boxes into their packed car, ready to leave the city behind. There’s a brief exchange, a few minutes in, between Joanna’s (Katharine Ross) husband Walter (Peter Masterson) and one of their kids: “I just saw a man carrying a naked lady!” “Well, that’s why we’re moving to Stepford.” After that, we don’t get much in the way of comedy for some time, aside from the occasional quip from Joanna or her friend Bobbie (Paula Prentiss).

As Joanna settles in and gazes out the car window, Walter climbs into the driver’s seat and says: “Terrific job you did there,” sniping at her for not getting everything out of the apartment.

Right away, something’s brewing under the surface of this relationship. Joanna’s not happy about moving and we soon learn that Walter didn’t give her much choice. On the eve of the first full day in Stepford, Walter comes home and “asks” for her thoughts on the Men’s Association in Stepford. Once it becomes clear that Walter is hiding something, she snaps at him:

Why don’t you ever once just tell me the truth? You pretend we decide things together, but it’s always you, what you want. You asked me if I wanted to move out here, and I found you’d already been looking at a house. You asked me if I liked this place, and I found you’d already made a down payment. Now you’re asking me about the lousy Men’s Association, and it’s quite obvious you’ve already joined. Why bother to ask me at all?

1975 Joanna comes across less confident, less sassy, and less outspoken than Book Joanna. Rather than a semi-professional photographer determined to make a name for herself, she’s a quiet but observant woman who’s insecure about her own talents and suffers an unequal relationship with her husband. Joanna’s sasslessness keeps the focus on her increasing paranoia and the sense of dread that underlies social interactions in the film.

But in sacrificing wit for the sake of horror, the film loses some of its impact. The sprinklings of humor that the film does offer are almost all straight from the novel--like Bobbie’s snappy dialogue (“What a pleasure to see a messy kitchen!” becomes “A messy kitchen! It’s beautiful!“) and Joanna’s bizarre exchange in the kitchen with Grade-A Creep Dale “Diz” Coba (Patrick O’Neal), who “like[s] to watch women doing little domestic chores.” When she asks why people call him Diz, he says he used to work at Disneyland.

Joanna: No, really.

Diz: That’s really. Don’t you believe me?

Joanna: No.

Diz: Why not?

Joanna: You don’t look like someone who enjoys making other people happy.

The 1975 film’s version of Walter, too, is altered for the sake of more explicit terror (and probably to get past the studio censors). Book Walter turns out to be an insidious “ally” who convinces Joanna that he will “infiltrate” the Men’s Association and help push for equality from the inside, but his plan is always to murder and replace her. When he returns from his first Men’s Association meeting in the middle of the night, aroused as he imagines his future sex-bot wife, Joanna wakes up to find him masturbating in bed next to her. She asks why he didn’t wake her and initiates sex, but unsatisfied by his real wife, Walter goes flacid. She manages to get him back up, and they have what she thinks to herself is the best sex they’ve ever had.

1975 Walter never pretends to be an ally like Book Walter. He’s more conflicted than Book Walter, but he’s still a villain. After his first meeting at the Men’s Association, 1975 Walter broods over what he plans to do, tears in his eyes, sitting by the fire, glass of whiskey in hand, but he still follows through with the plan to murder his wife.

The question of whether 1975 Walter can be trusted is answered in his voice, his body language, his actions, his treatment of Joanna, and his staring at her (or looking away). Rather than the false and dangerous sense of security that Book Walter leaves you with, 1975 Walter keeps you waiting for the other shoe to drop. It’s about the anticipation, the growing, inevitable dread. And it works--really well, actually--but there’s a reason people say the book is always better. Without Levin’s dark sense of humor, the film’s horror can’t convey the social critique in all it’s horrific absurdity.

Stepford, 2004

We mentioned the 2004 reboot of Stepford in our Fright Nights post:

[W]hile fun and at times smart, [it] ends up feeling like it’s mocking the original, disposing of the horror to make room for absurd comedy. The result is fun and often hilarious, but it also undermines the social commentary that a film made in 2004 should have been better positioned to deliver than the original.

I watched it again, and I feel mostly the same, but more harshly. This version is an insult to the original, and I don’t quite understand how it happened. The Muppet Show’s Frank Oz, who’s directed gems like The Dark Crystal (1982) and Little Shop of Horrors (1986), blames himself, going on record in a 2007 interview:

For the first time, I didn’t follow my instincts. And what happened was, I had too much money, and I was too responsible and concerned for Paramount. I was too concerned for the producers. And I didn’t follow my instincts, which I hold as sacred usually. I love being subversive and dangerous, and I wasn’t. I was safe, and as a result my decisions were all over the place.

Oz goes on to say the film was directionless, which is a shame considering the depth of the source material.

This version of Joanna (Nicole Kidman) is a successful, powerful reality TV exec. When a disgruntled man from one of her shows blames her for ruining his life and fires a gun at her while she’s onstage at a public event, the film plays it for laughs. Joanna then loses her job because, as her (now former) boss tells her,

That man, Hank. Right before he tried to kill you, he went to see his ex-wife and five of her new boyfriends… He shot all of them. The wife is in critical condition, and four of the guys are on life support.

The line is, frankly, exactly the kind of funny-horrifying I’m talking about, but the film ruins it by, again, playing it entirely for laughs.

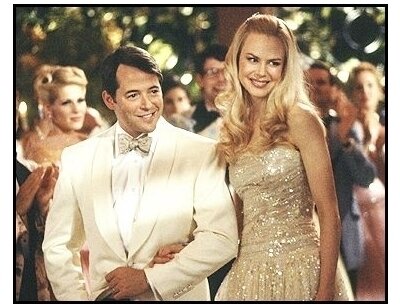

The movie then zips right past a mental breakdown, hospital stay, forgotten wedding anniversary, and a move to Stepford with 2004 Walter (Matthew Broderick), who’s weirdly sympathetic this round (because Ferris Bueller’s just charming, like Paul Rudd or Will Smith).

Instead of really trying to figure out what’s wrong with Stepford, 2004 Joanna’s on a mission to prove to her husband that she can be a good housewife, even if the other wives are creepy--exercising in full makeup and heels and gushing over Christmas catalogues at book clubs. Near the end of the film, Walter lays out his reasons for wanting a Stepford sex-bot:

Walter: Ever since we met, you’ve beaten me at everything. You’re better educated. You’re stronger, you’re faster. You’re a better dancer, a better tennis player. You’ve always earned at least six figures more than I could ever dream of. You’re a better speaker, a better executive. You’re even better at sex. Don’t deny it.

Joanna: I wasn’t going to.

The 2004 Stepford husbands feel emasculated by their successful wives, like they’re “the girl” in their relationships. And they’ve come to Stepford to get the trophy wives they’re entitled to. When we learn that head honcho Mike Wellington (Christopher Walken) is actually a Stepford sex-bot himself, we also learn that Claire Wellington (Glenn Close) is behind it all, wanting “a world where men were men and women were cherished and lovely,” after she catches her husband having sex with her research assistant and kills them both.

What’s more, the 2004 Stepford husbands don’t murder their wives but, instead, implant mind control chips in their brains. Then, 2004 Walter saves them all. He never turns Joanna into a sex-bot and instead smashes the mother machine or whatever, releasing all the Stepford wives from mind control.

The whole ending amounts to a tone-deaf reveal that perverts the feminist themes in Levin’s novel and the 1975 adaptation. (Not to mention that every bit of information in the film up to this point has been very explicit that the wives are being replaced with robots, or maybe turned into cyborgs. But somehow this ending just ignores all that and makes this completely nonsensical move instead.)

Obviously, the lack of horror isn’t the whole story behind the 2004 film’s failure, but it’s an important part. As absurd and as full of potential horror as 2004 Stepford is, it’s decidedly not horrifying. And without the horror, it doesn’t know where to go or what to be other than a silly, irreverent, aimless, sexist farce.

Get Out of Stepford

In the end, neither Stepford Wives film fully evokes the nuanced satire of Levin’s novel because one downplays the comedy, and the other eliminates the grotesque. In fact, the best adaptation of Levin’s feminist satire is not an adaptation at all. It isn’t even (primarily) about women or feminism.

But that’s an article for next week.