When the Wind Blows (1986)

This week, we’re expanding our Judgments section with another spoiler-free movie review. Reminder: we don’t do rating scales with stars or skulls or tomatoes. We just tell you our thoughts and whether we think something is worth your attention. Today, we’re giving you our take on the 1986 animated disaster movie, When the Wind Blows.

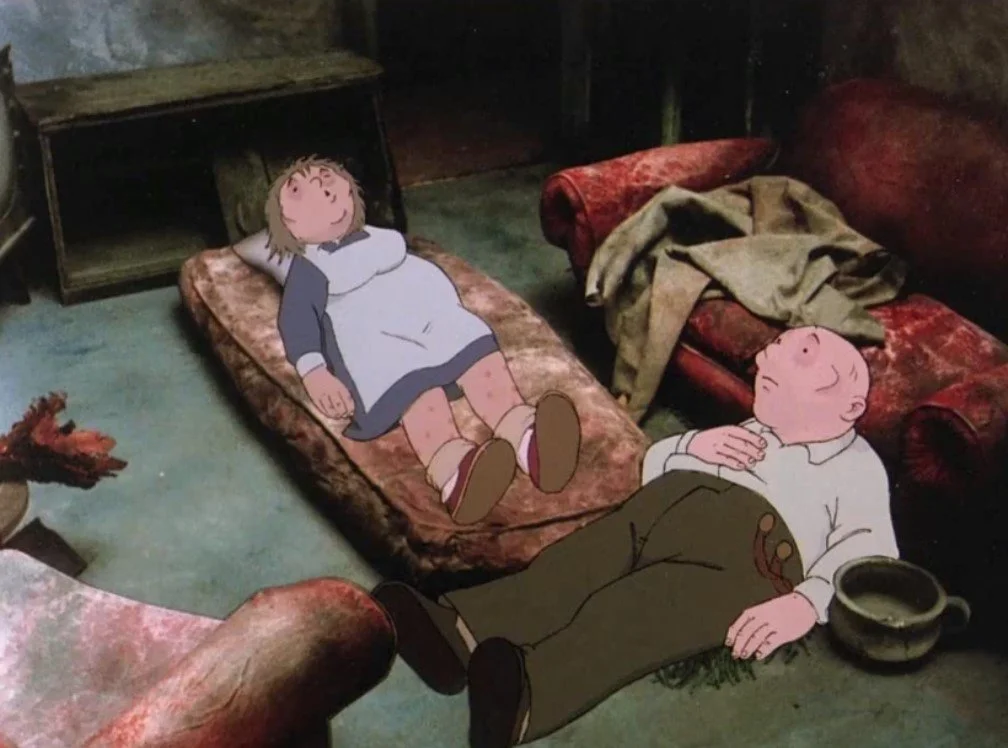

Based on Raymond Briggs’ 1982 comic book of the same name, When the Wind Blows tells the bleak and unrelentingly tense story of a doddering elderly couple who must survive a nuclear bomb dropped in rural England. The film is heavy-handed in some of its imagery and especially its music—arranged by Roger Waters of Pink Floyd—but in spite of these shortcomings, it manages to strike all the right emotional chords and succeeds surprisingly well.

The film’s director, Jimmy T. Murakami, an American-Irish animator and director of Japanese descent whose family spent time in a US internment camp during WWII, uses the film to explore the devastation of nuclear war wrought on innocent civilians who, in this case, are all but unaware of the terrible reality they face.

Set in the Cold War era, When the Wind Blows features an endearing but frustrating couple deluded by the British government’s Protect and Survive pamphlets. These, by the way, are real, government-produced videos and pamphlets advising civilians on civil defense, including how to prepare your home to withstand a nuclear blast. One piece of advice: take doors from other rooms (or use strong boards) and secure them against an inner wall at a 60º angle to create an “inner core or refuge.”

Jim Boggs (voiced by John Mills), the elderly husband, buys wholeheartedly into the pamphlet and everything he hears from the government. He always follows instructions, insisting that it’s “the correct thing!” His wife, Hilda Boggs (voiced by Peggy Ashcroft), on the other hand, is completely consumed with housework and cooking and bantering with Jim to even consider the potential nuclear fallout as a real threat.

The two live in a cottage in the English countryside. Though Jim frequently visits a nearby town to read newspapers and stay informed regarding the Soviet-Afghan War, they live in relative isolation from the world. Over the film’s first act, Jim grows increasingly anxious about nuclear war with the Soviet Union. He fixates on every shred of news, but only understands bits and pieces, and he often mixes up current politics and political figures with those of WWII.

With misguided but unwavering faith in the Protect and Survive pamphlets and the government, a worried but still cheerful Jim sets about fortifying their house while Hilda continues other domestic tasks. While Jim paints the windows white to deflect radiation, Hilda scolds him for splattering the curtains and not taking them down first. While Jim handily prepares the inner core or refuge, Hilda yells at him for taking all the doors down to do it. While Jim explains that they’ll need to stay securely in the inner core for fourteen days, Hilda makes very well sure he understands that she will be using the bathroom upstairs, thank you very much!

The couple’s chemistry not only works well, it feels very real. Even if you don’t have parents or grandparents or friends quite like them, you’ll almost certainly see people you know in their stubborn and pottering ways.

When the Wind Blows boasts fascinating and beautiful animation—a blend of hand-drawn, stop-motion, and crude ‘80s-era 3D animation, along with news footage from World War II and other historical events. The animation styles often clash, but in ways that seem intentional (if heavy-handed). Shots of nuclear warheads, tanks, submarines, and explosions are either computer generated or taken from newsreels and then butted up against the (also intentionally) mundane, family-friendly style in which Jim, Hilda, and a few scenes outside of their home are drawn.

To a limited extent, these clashing styles are effective, but at a certain point, they start to feel overdone, with the cringiest moments coming during the musical sequences. When we saw Roger Waters arranged the music and that the film featured a David Bowie song as its title track, we got excited—you should not. In the end, the music is a significant let-down, and mostly only disruptive to the film.

The best and most disturbing parts come from the absurd, yet frighteningly realistic, dialogue between our two isolated, out-of-touch characters. Here’s Jim’s take, early on, about who will win between the Soviets and the West:

Well, the Americans have tactile nuclear superiority, due to their IBMs and their polar submarines. But in the event of a pre-emptive strike, innumerate Russian hordes will sweep across the plains of Central Europe. Then the US Technical Air Force will come roaring in with their Superhawks, B-17 s and B-19s, bristling with guns! Terrifically armed!

They'd raze the Russky defenses to the ground. Then the marines would parachute in and round up the population. After that, the big generals would go over... like... Ike and Monty.

Then the Russians would capitulate, and there would be a condition of surrender. Then they'd install free and fair elections. One man, one vote. And women too, nowadays, of course.

And thus, the Communist threat to the Free World would be neutrified, and democratic principles would be instilled throughout Russia, whether they liked it or not. That's the world scenario as I see it, at this moment in time.

Hilda responds only, “Monty. Wasn’t he in the war?” Then the two go off on a tangent trying to remember who was in WWII, some forty years go. Then the conversation gets twisted in with a tangent about savings certificates and medical cards until Hilda asks, “Who’s in charge of the Russians, dear?” After some reaching around for names, Jim settles on, “Khrushchev. Yes, that’s right. B and K. Bulgaria and Krushchev, that’s them. And that bloke Marx has got something to do with it.”

Written here, the conversation seems almost endearing in how out of touch and unfocused it is. Onscreen, though, in the context of all that’s happening, it leaves you with a deep sense of dread over their inability to see the seriousness of the situation. That dread only grows more intense as the film goes on.

Even after the drop of the bomb (not a spoiler, by the way—you know going in that this is inevitable), we get the slowest of slow-burn horror. It’s agonizing and terrible to watch these two continue to use those government pamphlets as their only guide to navigating the fallout of a nuclear bomb. Their situation is made all the more tragic by their genuine expectation that everyday services like milk deliveries will continue.

It’s notable that this couple, who, despite their weirdly fond memories of hanging out in homemade bomb shelters during WWII, can’t fathom a disaster on the scale of Hiroshima befalling them. Jim explains that they should wear white during the fallout:

People in Hiroshima with patterned clothes got burned where the pattern was, and not so much on the white bits. Even the buttons showed up.

Hilda replies, maddeningly:

Yes, but they were Japanese. … You’re not going to wear that nice new one I gave you for Christmas? I don’t want that spoiled! You can wear your old clothes for the bomb and save the best for afterwards.

In Jim’s head is a theatrical production, a war movie with a good vs. evil narrative, like Churchill and Hitler in WWII. The reality, though, is a less clear-cut plot of the Powers That Be doing whatever they want, at any cost, nevermind the casualties. And in Hilda’s head is every silly little thing she’s used to worrying about, but not a trace of the brutal reality she and Jim need to confront.

To really appreciate this movie, you need to pay close attention to the dialogue. At first, it’s just the amusing, mundane banter of a doddering old couple, but as the film goes on, all that emotionally charged, melodramatic footage amplifies the absurdity of their conversations until that humor becomes horrific. Mundane reality becomes swallowed up by disorienting madness and the cruelty of war for two people living in an isolated world of delusion fed by decades of pro-war, pro-government propaganda—a theme that resonates disturbingly well with the political realities of the United States today.

At its core, When the Wind Blows is extremely affecting and powerful, if heavy-handed and poorly scored. For all those moments of musical cringe, though, the film is beautifully animated, fascinating to watch, and full of excellently crafted dialogue. And despite their dodderingness, Jim and Hilda come across as deeply sympathetic characters you can’t help but grow attached to. It may not be good for a movie night with friends or a date night with your partner, but When the Wind Blows is definitely worth your time.