Missing the Messy Bits: A Comparison of Fright Nights

BEWARE SPOILERS

We go into every post assuming you’ve already watched the film being discussed.

The original Fright Night (1985) is available for free on Pluto TV as of this writing (4/18/2021).

Remakes and reboots are often expected to retain all the best and fix all the worst parts of the original. Take the successful case of the 1997 TV reboot of 1992’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer, both by that guy who worked on The Cabin in the Woods and used to make good movies and TV shows but who was also really horrible to some of the actors and crew members who worked for him. Most of the world knows Buffy as Sarah Michelle Gellar, not Kirsty Swanson, for a variety of reasons, but in part because the TV version tones down the over-the-top Valley girl-ness of movie Buffy and re-envisions large parts of what would come to be the Buffyverse. TV Buffy also, thankfully, scraps all the pedo parts with adult men following teenage girls into locker rooms and instead turns the supporting cast into a “Scooby Gang” devoted to helping their friend in fulfilling her Slayerly destiny.

There’s also My Bloody Valentine (1981), whose ‘09 remake decided a group of men and women in their twenties obsessing over a Valentine’s Day dance and a serial killer bent on murdering everyone if they have that dance was rather silly. Cutting that whole business in the remake was an act of mercy on the viewer. Instead, we get all the splatter kills and jump scares and iconic imagery that gave the original its cult status and a lot less of the over-the-top backstory. We also get the addition of eye-roll-inducing 3D effects because, for some reason, the late 2000s and early ‘10s were obsessed with 3D glasses.

Of course, remakes come with risks too. 2004’s reboot of 1975’s The Stepford Wives, while fun and at times smart, ends up feeling like it’s mocking the original, disposing of the horror to make room for absurd comedy. The result is fun and often hilarious, but it also undermines the social commentary that a film made in 2004 should have been better positioned to deliver than the original. The big reveal at the end also undercuts the story’s central horror by erasing the consequences of the evil going on in Stepford.

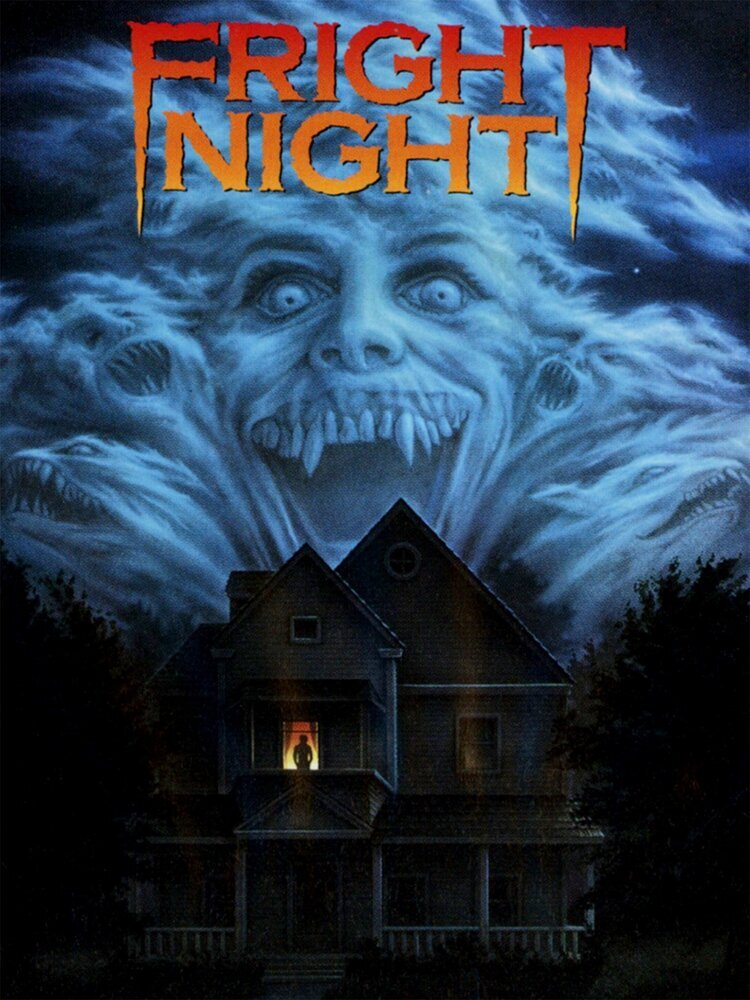

Then there’s the remake of Tom Holland’s Fright Night (1985), which is what we’re going to talk about today. Directed by Craig Gillespie, the 2011 film revises pretty much every character from the original. It cuts out the creepy sexualized treatment of Amy. It rebalances the various genres at play in the original, favoring a more action-oriented approach over Holland’s self-aware campiness and references to horror movies of yore. The remake adds depth to the character relationships in the original, as well as a welcome, if underdeveloped, criticism of the misogyny expressed by characters throughout. The result of all that revision and rebalancing is a movie that responds to the criticism of ‘80s slashers offered in the original and promises, not a return to campy vampire horror that Holland’s Fright Night mockingly admires, but instead a modernized approach to the very slasher genre the original film rejects.

In the process, Gillespie’s film offers greater depth to character relationships than the original and a hell of a lot more action. It also gives more agency to female characters, most notably Amy (Amanda Bearse/Imogen Poots), and disposes of the glamorized portrayal of a grown man preying on a young girl. But the remake sacrifices important parts of “Evil” Ed (Stephen Geoffreys/Christopher Mintz-Plasse) and Peter Vincent (Roddy McDowall/David Tennant). And, it lacks much of the timing, humor, and all-around charm present in every molecule of the original, from score to sound to visuals to dialogue--although, the late Anton Yelchin as Charley and Tennant as Peter Vincent both make up for an immense amount of charm and quirk lost elsewhere.

Consider the beginning of the ‘85 film, when the words “Fright Night” appear on screen. As the F and the T grow into fangs, the score comes in with a perfectly timed orchestral stab. Consider too all the other musical flourishes, nods to horror cannon like Rear Window (1954) and of course Dracula (1931), and lines like this oft-quoted classic from the original Peter Vincent after he loses his job as TV horror host, getting at the movie’s underlying meta-horror argument:

Nobody wants to see vampire killers anymore, nor vampires either. Apparently all they want are demented madmen running around in ski masks, hacking up young virgins.

Vampires Are Pedophiles

Before we really get into this, can we all agree that, for vampires who’ve been around potentially hundreds of years, pretty much everyone is a child, including the teenage girls they fall deeply in love with? Because the amount of romantic tales featuring hundred-year-old vampires seducing young girls is pretty gross.

Given that modern vampire lore is often traced back to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (of course, the mythology goes much further), the Original Vampire Creep, the vampire-as-sexual-predator trope makes sense, and Jerry Dandridge is an appropriately inappropriate modern iteration in that disgusting line. (Except in that nightclub scene from the original. That’s just inappropriately inappropriate, iconic and beloved though it may be. But we’ll get there in a second.)

Ever since the introduction of broody, romantic, and occasionally sympathetic Anne Rice vampires, there’s been a steady tide of fanged undead pedos: from the vampire Lestat to Buffy’s Angel (she was at least over eighteen with Spike) to a certain sparkly vampire who poses as a high school student and engages in a deeply questionable relationship with a teenage girl.

With that in mind, one of the best decisions in the Fright Night remake is to subtract Jerry’s creepy infatuation with teen Amy over her resemblance to someone he once loved. The original Jerry lays claim on her in a patently gross way that the film, rather than presenting as gross, glamorizes in an unnecessarily drawn out scene in which he basically (ahem) turns her into a woman.

Here, the original gives us a problematic depiction of the seduction of a minor, offering a romanticized view of assault and coercion. Because, you know, the guy’s an immortal being with weird vampire-charm. And Amy’s a high school girl. Emphasis on girl.

Gillespie basically scraps that psycho-sexual dance sequence, from which Amy emerges “sexually awakened” after a transition from school girl to young woman--and eventually a clown-mouthed monster. Even her hair, in a few transformational shots, goes from short and plain and to a teased out, stylized ‘80s hairdo. The next time we see her, an hour or two later, she’s grown it out to a long red-blonde mane.

Of course, the remake doesn’t cut the iconic nightclub scene altogether, and Amy does fall victim to Jerry in an equally creepy way, but it’s not because he’s fixated on her as his future bride or whatever. He’s a predator, pure and simple. More importantly, the scene is shorter and doesn’t glamorize his sexual conquest with close-ups of his hands running over her body and a transformation sequence of Amy becoming a woman. The changes make the whole scene less gross and show Jerry in an appropriately inappropriate light.

Focusing on Jerry as a bloodthirsty beast rampaging through Charley’s Las Vegas suburb, 2011’s Fright Night offers up an argument about predatory behavior and misogyny by having all the characters we’re not supposed to like make crude and sexist remarks about women:

Jerry: Your girl, Amy, she’s ripe. I bet there’s a line of guys dying to pluck that. Your mom too. You don’t see it. Or maybe you do. But she’s putting it out. It’s on you to look out for them.You up for that, guy?

Charley’s Douchey Friends: Did you find a frickin’ genie lamp, man? Make a sacrifice to the hot ass gods? How do you get that [Amy’s hot ass]?

Peter Vincent (before he redeems himself), referring to a colleague in his Vegas magic act when he first meets Charley: I fucked her. Filthy.

Evil Ed (once he’s, um, evil): You know, I expected more from you Brewster. Girl’s made you lazy in the head. Pussy’ll do that.

The critique is a bit simplistic and easy to miss if you’re not thinking to yourself, Now which characters said all those sexist things, and are we supposed to like them? Putting all that in the mouths of villains, an arrogant hack (before he redeems himself), and shallow, teenaged bullies is a passive way of saying misogyny is bad without really grappling with it. Sure, that’s better than not saying anything at all, but it would be nice to see a character at least push back against all the woman-hating.

The original vampire terrorizing the neighborhood, Jerry Dandridge (Prince Humperdink (Chris Sarandon)) is an imposing but slippery villain trying to avoid detection. In contrast, 2011’s Jerry the vampire (Colin Farrell (not Prince Humperdink)) is a monstrous, bloodthirsty, misogynistic, and relentless predator who rips gas lines out of the earth with his bare hands, throws motorcycles through the rear windows of speeding cars, and will burn down entire communities so he can feed. In exchanging the subtle gaslighting employed by Sarandon’s Jerry for the uninhibited and unstoppable force of Farrell’s Jerry, we gain heightened terror and adrenaline, but we lose that sense of subtle insidiousness and complex villainy.

We also get a reinvented Amy, one who’s tougher, less naïve, and less susceptible than her original counterpart to vampiric seduction. Where ‘85 Amy tried to bribe Peter Vincent with a $500 savings bond to convince Charley that vampires aren’t real, 2011 Amy quickly realizes that he’s not crazy and launches herself into the fight--not that she has much of a choice, what with Jerry blowing up Charley’s mom’s house and all.

“You’re So Cool, Brewster!”

Of all Gillespie’s revisions, his changes to character are clearly the most consequential. The best and worst character changes, in our view at least, all come with “Evil” Ed.

In the original film, Ed is simultaneously great fun and cringeworthy--a bizarre but fascinating character whose sometimes perplexing dialogue and wild laughter, at times, lend chaos to horrifying moments, and at other times, trivialize otherwise powerful scenes.

Geoffreys’ ‘85 Ed is a strange mash-up of character types. If you remember Tim’s breakdown of horror movie character archetypes in his post on The Cabin in the Woods, you can probably peg Ed as the Fool, akin in some ways to Scream’s Randy and Stu, as Meg noted a couple weeks ago. He also shares some Scholar responsibilities with Peter Vincent as the resident vampire movie expert whose knowledge, even in his tragic fall, helps Charley overcome vampire Jerry.

(And yeah, we said “tragic fall.” Look, Geoffrey’s Ed may be over-the-top, and sure, he’s turned into a vampire by Prince Humperdink, but the dialogue in that scene and Geoffreys’ performance in it are surprisingly tender and tragic, and his de-transformation during his death sequence is gut-wrenching, replete with constant cuts to McDowell’s agonized expression as he watches in horror.)

Beyond standard horror movie archetypes, Ed fills other common types, and some of them clash. Other than Charley’s girlfriend Amy, Ed seems to be his only friend. But he’s also something of a bully, as well as a victim and, as 2011 Ed reminds us, a “spaz.” There’s a ton of potential for character depth here--just think of that tragic fall stuff--but an overemphasis on spazzy quirks turns him into a caricature, which is great fun at times, but it also disrupts some emotionally charged scenes.

In Gillespie’s Fright Night, Ed is remolded as a nerdy kid who, alongside the missing Adam Johnson (Will Denton), used to be one of Charley’s best friends. They would dress up in costumes and film each other LARPing as characters with names like Squid Boy. (LARPing, in case you’re not up on the latest ways to live life to the nerdiest, is this thing where people dress up like elves or superheroes or space pirates or whatever and play out role-playing games live--hence, Live Action Role-Playing.) Less of a Fool and no longer a bully, Mintz-Plasse’s Ed is a smart, inquisitive kid made fun of by Charley’s new friends. He’s been pared down to fit just two basic roles: Investigator and Outcast.

Convinced that Charley’s neighbor is a vicious, fanged killer responsible for the growing absences at school, he tries to enlist Charley as a fellow Investigator. Charley dismisses him and Yelchin’s performance shows deeply felt guilt left unspoken until Evil Ed--that is, Ed as evil vampire--tells him outright, “Oh, do I got a problem. You turned me into this. You let him get to me.”

Only after Charley commits one of the few acts of real consequence in the remake, staking his lost former friend through the heart after a particularly gruesome fight, does non-evil Ed seem to return and, as he burns into dust, relieve Charley’s guilt: “It’s okay, Charley. It’s okay.”

Embedded as they are in the relentless action of the film’s second half, though, these bits of dialogue are easy to miss, which is unfortunate, given how well they define the central tragedy of Charley and Ed’s relationship.

Rather than saddling Ed with a pile of roles usually delegated out one or two per character, Gillespie’s film opts for a simpler Ed, one who helps streamline the story, fits better into the film as a whole, and gives depth to his relationship with Charley. But there’s something missing.

One of the reasons ‘85 Ed fills all those roles--Fool, Scholar, Bully, and Outcast--is that he’s not typed. He’s what you’d call a multi-faceted character in a literature or film studies class. It means he’s complicated, flawed in interesting ways, messy--you know, like real-life human people are messy. The revised Ed, typed mainly as an Investigator, helps hold the film together and moves the plot along, but he loses some of the complexities of the original character.

Missing the Messy Bits

Other characters, too, underwent significant makeovers. Charley’s mom, renamed from the original’s Judy (Dorothy Fielding), now called Jane (Toni Collette), is an assertive woman and an attentive mother who doesn’t offer her son valium (which we kind of miss from the ‘85 version--it’s such a weirdly great moment--but that’s beside the point). In addition, David Tenant’s mid-career Vegas magician Peter Vincent presents as a different kind of bitter than Roddy McDowell’s washed-up horror movie hero fired from his job as a late-night horror host.

Inspiration for 2011 Peter Vincent seems to come largely from Tennant’s then-recent tenure on Doctor Who. (Sounds fun, right? The Doctor as a would-be vampire hunter/Vegas showman? Sign us up! But it doesn’t quite work. We need to really dislike this guy at first. He’s a hack, he’s a misogynist, and he’s dismissive of a young man begging for help, all things that feel wrong coming out of the Doctor’s mouth.)

The character revisions are a mixed bag. The updated versions fit better into the narrative, but they’re missing some of the subtlety and complexity hiding beneath the campy surface of the original characters. And the action sequences, while fun, often distract from the more moving and thoughtful parts of the film--and the plasticy, video-gamey computer animation, particularly during the car chase, doesn’t help.

Nonetheless, the remake’s answer to the original’s criticisms of the slasher genre is respectable. But in revising the characters down to simplified types playing clearly defined roles, it’s revised its own genre. That shift leads to a departure from the original’s comic timing and from its charming homage to classic horror in favor of a brutal, terror-fueled vampiric nightmare. In re-envisioning the characters, Gillespie cuts a lot of messy bits, largely to good effect. But, as with many cult classics, some of those messy bits are really wonderful, and you miss them when they’re gone. And, as in other artforms, often the most interesting bits are messy, especially in a meta-horror/comedy touchstone like 1985’s Fright Night.