On Lyric Horror

In the late 1800s, beginning with the first moving pictures, a rich subgenre of horror movies, full of dreamlike images and bizarre characters and narratives, started unfolding on the cinematic screen. The earliest examples, like “The Haunted Castle” (1896), can feel at times more like tech demos than intricate works of art, but even these show a surreal quality that later films, like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Phantom Carriage (1921), and Nosferatu (1922) would expand upon to create features that unravel like creepy lyric poems, brimming with questions of memory and perception. Over the decades, those themes have continued to grow in films like Carnival of Souls (1962), House (1977), Santa Sangre (1989), Donnie Darko (2001), and Mother! (2017).

Often driven by traumatic experiences, events in these lyric horror movies are more metaphorical and allegorical than literal. They approach subjects upside-down and sideways, making associative leaps between events and ideas. Unlike traditional narratives, which describe who did what, why, and what happened after?, lyric horror, like other lyric cinema, ignores—and often intentionally muddles—these questions, preferring to fixate on impressions, psychological states, and artful depictions of character, setting, and scene.

Our next series of Dissections will focus on this often peculiar and disorienting subgenre. We’ll rummage through the guts of films with dysfunctional narratives, hyperbolic imagery, and a penchant for psychosexual melodrama. Right now, though, we’re going to ramble a bit and try to work out our own thoughts about lyric horror before we look more closely at specific films. Think of this Judgment as a first draft of our thoughts on lyric horror, which we’ll expand with each new Dissection in the series.

(In fact, think of this kind of essay as a new kind of Judgment article. The Pre-Dissection Thinky-Definey Essay, in which we think our half-informed thoughts and define some of the terms and ideas we’ll explore in the series.)

*

A minute ago, we called lyric horror a subgenre of horror movies. That’s basically right, but it’s more technical and precise to say that lyric horror is composed in the lyric mode.

At the root of the word “lyric” is “lyre,” as in the musical instrument most associated with Ancient Greece. When you describe something as “lyric,” you’re saying, in part, that there’s something musical about it. For a very long time, humanity, across cultures—and poets especially—made this observation about poetry. Take Aristotle. He pegged musicality to a specific kind of poetry, separating the lyric—short, highly formal musings and meditations accompanied by a lyre or other music—from two other two kinds of poetry. Epic poetry unfolded into grand mythological stories about heroes and gods, and dramatic poems offered character-driven dialogues and monologues.

Over time, the term “lyric” moved away from literal music to center on the formal qualities of lyric poems, like rhyme, rhythm, and alliteration. Eventually, those expanded to include qualities that aren’t exactly musical, like line breaks and the use of persona (in which a poem inhabits a specific character’s point of view and figure on their emotions, attitudes, and impressions, as opposed to telling a story or presenting a dramatic scene). These days, if we’re being academic-y and precise, a poem written in the lyric mode refers to a highly structured and formal piece of writing that uses a specific voice and experience to convey perception, feeling, and memory. The majority of lyric poems are also lineated.

(That means they contain

breaks at the ends

of their lines,

like this.)

Like “lyric,” the word “mode” is also a musical term that’s accumulated meanings over the history of Western music. Generally, though, those meanings come down to artistic mood and emotional tone. When applied to non-musical artforms, the term “mode” also relates to genre and subgenre, as well as tropes and archetypes. Mode, understood very simply, defines the voice, tone, attitudes, and general character of a piece of art. Just as Aristotle described epic, dramatic, and lyric poetry, Shakespearean scholars describe tragic, comic, and historical plays—theatrical modes.

Essays have modes too. In an introduction to the Seneca Review’s fall 1997 special issue, titles “The Lyric Essay,” then editor Deborah Tall and associate editor John D’Agata defined lyric essays as

“poetic essays” or “essayistic poems” … [that] forsake narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation.

The lyric essay, they explain, indulges poetry’s

density and shapeliness, its distillation of ideas and musicality of language.

So, the lyric poem wants to become music. And the lyric essay wants to become poetry that wants to become music.

In fiction, the movement toward lyricism kicks into high gear in the early-to-mid 1900s with Modernist writers like Stephen Crane and Willa Cather, alongside playwrights like Samuel Beckett and, later, Jean Genet. As with writers of lyric poems and essays, lyric fiction authors produce works that echo the structures and techniques of poetry, tapping into those same musical qualities.

Often, these authors push against traditional plots—stories of people doing things, of action and consequence, of narrative throughlines. Instead, they sketch perceptions and emotions in the descriptive and musical lyric mode.

*

So, if lyric writing is all about specific perspective, imitation of music, and ditching narrative for meditation and weirdness, then the same goes for lyric horror movies. Film, though, has actual, literal sound and music to guide an audience’s emotional reaction—even silent films were typically accompanied by live music. Rather than the shared reality that the camera inhabits in films with traditional narratives, lyric horror often reflects a specific character’s perception of the world through metaphorical transformations of what’s happening in the literal sense. Think psychedelic, surrealist, and expressionistic films here, like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Carnival of Souls (1962), Santa Sangre (1989), Jacob’s Ladder (1990), and The Wolf House (2018). A story is happening, but it’s twisted by the warped or confused perspective of its main character.

According to Tall and D’Agata, a lyric narrative “often accretes by fragments, taking shape mosaically —its import visible only when one stands back and sees it whole.” The point is not to present a clear, concrete, and linear story, but to encourage rumination and invite interpretation, to favor form and artifice over realism.

This feature of lyric storytelling fits nicely with the horror genre because our natural reaction to horrific things is often to turn away. When we talk of death, we speak in euphemism about people who have “passed on” or “gone to a better place.” In our news feeds, we tend to scroll past images of war-torn Ukraine, Syria, and Yemen. Most of us prefer not to know the details of animal life in factory farms. Like Hitchcock said, “Reality is something that none of us can stand, at any time.”

Lyric horror is full of repressed perspectives and suppressed realities. From Alex Jodorowsky’s main character Fenix in Santa Sangre, who is driven insane when he sees his father brutalize his mother, to Jacob Singer in Jacob’s Ladder, a Vietnam veteran suffering what he initially believes to be PTSD, the characters and perspectives in lyric horror are overwhelmed by traumatic and terrifying events. Audiences experience the worlds of these films through warped lenses. Perspective and plot become messy and confusing as metaphor and allegory overtake them.

*

Another quality of lyric horror: telling stories by way of omission.

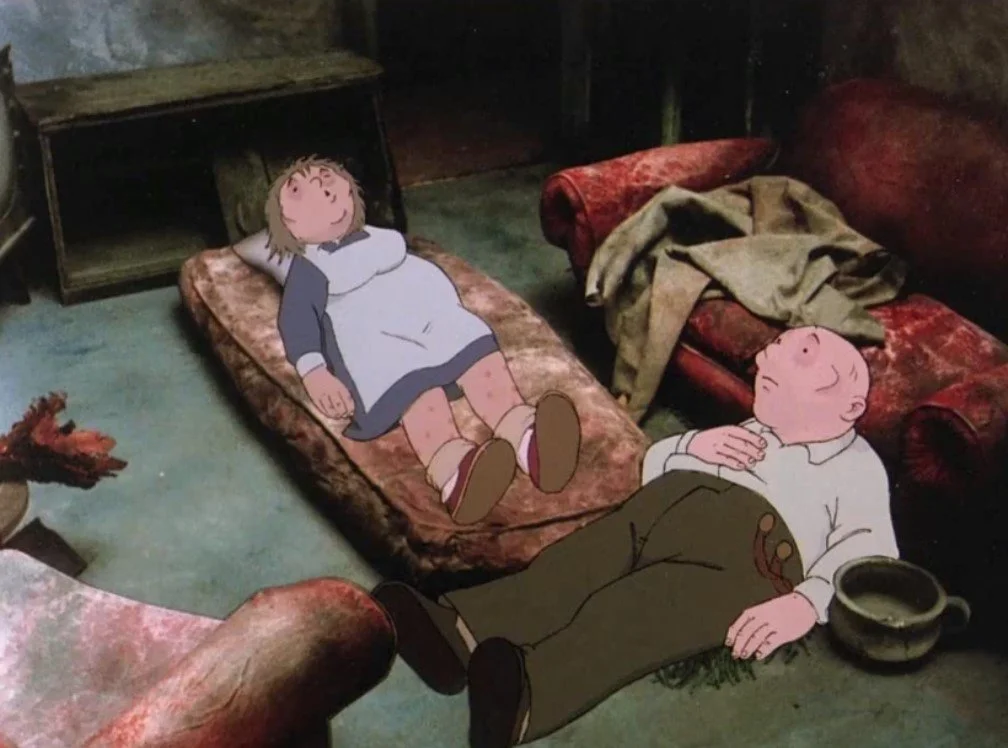

Take Cristobal León and Joaquín Cociña’s dark and disturbing stop-motion picture, The Wolf House. In it, the filmmakers circle around real, fascist-fueled Chilean history while presenting a deeply twisted version of “The Three Little Pigs.” The filmmakers don’t ever directly reveal the traumas of their characters, maybe because the truth we imagine is more terrifying than anything they could depict onscreen. Regardless, León and Cociña trust viewers to work out the shape of the movie’s narrative themselves.

Full of disorienting and unsettling visuals, and told through the warped perspective of the Wolf, the slanted approach to its traumatic subject matter forms a narrative-shaped hole at the film’s center. As the story unfolds, an attentive and perceptive viewer will come to recognize the shape of that narrative black hole and understand the dark and horrific reality never shown or described onscreen .

Like The Wolf House, lyric horror depicts escapist fantasies and nightmares as if they were real, turning internal experience into external truth. They often fixate on traumatic subjects that defy direct representation and must be approached askew. The films follow protagonists who can’t come to terms with truths they find too terrible to face. To reflect this, the filmmakers often leave out those hidden truths, instead tracing their outlines through their characters’ metaphor-filled, often Freudian delusions.

The lack of clear narrative can make the heavy subject matter of films like The Wolf House easier to navigate and engage with, but it can also alienate viewers, leaving them wondering, like everyone who’s ever seen Donnie Darko, what the hell just happened. Even at its most confusing, though, good lyric horror pushes audiences to feel things they often can’t fully express, which brings us to one last point.

As lyric essays and stories imitate poetry imitating music, so too with lyric film. But why such highly formal poetry? Why music? The formal elements of poetry, like music, express what cannot be expressed fully in words. They speak to ancient parts of the mind that don’t think in language but in emotions and impressions, the places where dreams live. Imitating music, the lyric mode uses rhyme, rhythm, lineation, persona, and other formal elements to speak to those ancient parts of our minds. Lyric horror, in particular, traces the imprints left by deep-seated traumas, bizarre nightmares, and all-consuming fears, anxieties, and perversions.

Look forward to some weird shit, folks.